Epicureanism

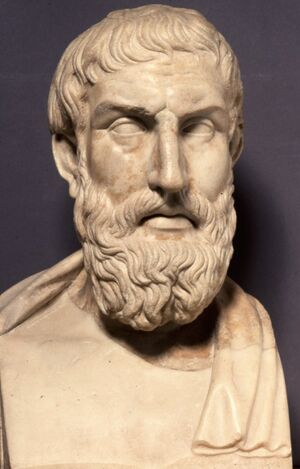

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) was an ancient Greek materialist philosopher and the founder of the philosophical school of Epicureanism, a doctrine centered on the pursuit of happiness through the cultivation of modest pleasures, knowledge, friendship, and the absence of pain (ataraxia). Within Marxist philosophy, Epicurus is recognized as a progressive materialist thinker whose ideas anticipated core elements of dialectical and historical materialism.

Life and Historical Context

Epicurus was born on the island of Samos and later established his philosophical school in Athens, known as The Garden, which stood in opposition to the dominant idealist traditions of Platonism and Aristotelianism. Epicureanism promoted a philosophy accessible to all, including women and slaves—an early, though limited, form of egalitarianism.

Epicurus stood firmly in the materialist camp, asserting that all phenomena could be explained by the interaction of atoms in the void—an idea inherited from Democritus, whom Marx described as one of the first dialectical materialists.

“Democritus and Epicurus are the only two Greek philosophers who can be said to have actually brought a materialist philosophy to its true and consistent form.”[1]

Philosophical Doctrine

Atomism and Materialism

Epicurus advanced Democritean atomism by introducing the concept of the clinamen (swerve), a random deviation in the motion of atoms that allows for the emergence of novelty and human freedom. This anti-deterministic view of nature was of significant interest to Karl Marx, who devoted his doctoral thesis to "The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature" (1841).

“Epicurus…"is the true radical Enlightener among the ancients.” [2]

In contrast to mechanical determinism, Epicurus affirmed the contingency of events in nature, which aligned with the dialectical insight that change arises through contradictions and unpredictability in material processes.

Ethics and Social Life

Epicurean ethics centered on pleasure (hedone) as the highest good—but not in the vulgar or hedonistic sense. For Epicurus, true pleasure was achieved through the absence of pain, tranquility of mind, and rational understanding of nature.

While his rejection of politics and active engagement in the polis reflected the limitations of Greek class society, his communal way of life prefigured aspects of socialist collectivism.

Epicureanism and Revolutionary Materialism

Although Epicureanism did not advocate class struggle or proletarian revolution, Marxist thinkers have recognized it as an early form of progressive materialism, opposed to religious superstition and idealism.

Marx, in particular, saw in Epicurus a philosopher who defended individual autonomy against metaphysical tyranny—an aspect that resonates with the critique of ideology and the struggle against religious obscurantism in the Marxist tradition.

Marx’s Doctoral Thesis

Marx’s early engagement with Epicurus revealed his attempt to historicize and radicalize ancient materialism. Marx emphasized that Epicurus, unlike Democritus, recognized the importance of human subjectivity and freedom within the material world.

“The atom of Epicurus is different from the atom of Democritus in that it contains in itself the principle of motion.” [3]

This notion of internal motion and spontaneity anticipated Marx’s later emphasis on praxis—the unity of theory and revolutionary action.

Legacy in Marxist Thought

Epicureanism, as interpreted through the lens of historical materialism, is a philosophical ancestor of atheism, scientific socialism, and critique of ideology. It served as a foundation for later developments in Enlightenment thought and influenced the materialist conception of history developed by Marx and Engels.

“The materialism of Epicurus was the foundation on which the whole modern materialist movement was built.” [4]

Lenin reaffirmed the historical importance of ancient materialism, including Epicureanism, as a class-based philosophical weapon in the ideological struggle between science and superstition.

Criticism and Limitations

From a Marxist standpoint, Epicureanism remained limited by its individualism and detachment from collective social practice. Its retreat from political life reflected the decay of the Greek polis and the absence of a revolutionary proletariat.

Nevertheless, Epicurus’s attack on religion, his rational understanding of nature, and his early materialism represent historically progressive ideas that contributed to the ideological foundations of Marxism.

See Also

References

- ↑ Karl Marx, Doctoral Dissertation, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature (1841)

- ↑ Karl Marx, Doctoral Dissertation, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature (1841)

- ↑ Karl Marx, Doctoral Dissertation, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature (1841)

- ↑ Friedrich Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886)