Library:Industrialisation of the country and the Right Deviation in the C.P.S.U.(B.)

Industrialisation of the country and the Right Deviation in the C.P.S.U.(B.) | |

|---|---|

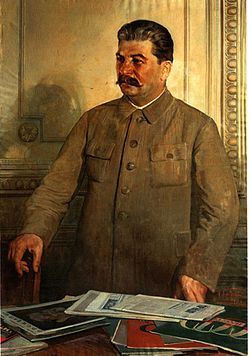

Joseph Stalin, author. | |

| Written by | Joseph Stalin |

| First published | November 19, 1928 |

| Source | Link |

| Audio version | Link |

Industrialisation of the country and the Right Deviation in the C.P.S.U.(B.)

I shall deal, comrades, with three main questions raised in the theses of the Political Bureau.

Firstly, the industrialisation of the country and the fact that the key factor in industrialisation is the development of the production of the means of production, while ensuring the greatest possible speed of this development.

Next, the fact that the rate of development of our agriculture lags extremely behind the rate of development of our industry, and that because of this the most burning question in our home policy today is that of agriculture, and especially the grain problem, the question how to improve, to reconstruct agriculture on a new technical basis.

And, thirdly and lastly, the deviations from the line of the Party, the struggle on two fronts, and the fact that our chief danger at the present moment is the Right danger, the Right deviation.

I. The Rate of Development of Industry

Our theses proceed from the premise that a fast rate of development of industry in general, and of the production of the means of production in particular, is the underlying principle of, and the key to, the industrialisation of the country, the underlying principle of, and the key to, the transformation of our entire national economy along the lines of socialist development.

But what does a fast rate of development of industry involve? It involves the maximum capital investment in industry. And that leads to a state of tension in all our plans, budgetary and non-budgetary. And, indeed, the characteristic feature of our control figures in the past three years, in the period of reconstruction, is that they have been compiled and carried out at a high tension. Take our control figures, examine our budget estimates, talk with our Party comrades—both those who work in the Party organisations and those who direct our Soviet, economic and co-operative affairs—and you will invariably find this one characteristic feature-everywhere, namely, the state of tension in our plans. The question arises: is this state of tension in our plans really necessary for us? Cannot we do without it? Is it not possible to conduct the work at a slower pace, in a more "restful" atmosphere? Is not the fast rate of industrial development that we have adopted due to the restless character of the members of the Political Bureau and the Council of People's Commissars?

Of course not! The members of the Political Bureau and the Council of People's Commissars are calm and sober people. Abstractly speaking, that is, if we disregarded the external and internal situation, we could, of course, conduct the work at a slower speed. But the point is that, firstly, we cannot disregard the external and internal situation, and, secondly, if we take the surrounding situation as our starting-point, it has to be admitted that it is precisely this situation that dictates a fast rate of development of our industry.

Permit me to pass to an examination of this situation, of these conditions of an external and internal order that dictate a fast rate of industrial development.

External conditions. We have assumed power in a country whose technical equipment is terribly backward. Along with a few big industrial units more or less based upon modern technology, we have hundreds and thousands of mills and factories the technical equipment of which is beneath all criticism from the point of view of modern achievements. At the same time we have around us a number of capitalist countries whose industrial technique is far more developed and up-to-date than that of our country. Look at the capitalist countries and you will see that their technology is not only advancing, but advancing by leaps and bounds, outstripping the old forms of industrial technique. And so we find that, on the one hand, we in our country have the most advanced system, the Soviet system, and the most advanced type of state power in the world, Soviet power, while, on the other hand, our industry, which should be the basis of socialism and of Soviet power, is extremely backward technically. Do you think that we can achieve the final victory of socialism in our country so long as this contradiction exists?

What has to be done to end this contradiction? To end it, we must overtake and outstrip the advanced technology of the developed capitalist countries. We have overtaken and outstripped the advanced capitalist countries in the sense of establishing a new political system, the Soviet system. That is good. But it is not enough. In order to secure the final victory of socialism in our country, we must also overtake and outstrip these countries technically and economically. Either we do this, or we shall be forced to the wall.

This applies not only to the building of socialism. It applies also to upholding the independence of our country in the circumstances of the capitalist encirclement. The independence of our country cannot be upheld unless we have an adequate industrial basis for defence. And such an industrial basis cannot be created if our industry is not more highly developed technically.

That is why a fast rate of development of our industry is necessary and imperative.

The technical and economic backwardness of our country was not invented by us. This backwardness is age-old and was bequeathed to us by the whole history of our country. This backwardness was felt to be an evil both earlier, before the revolution, and later, after the revolution. When Peter the Great, having to deal with the more highly developed countries of the West, feverishly built mills and factories to supply the army and strengthen the country's defences, that was in its way an attempt to break out of the grip of this backwardness. It is quite understandable, however, that none of the old classes, neither the feudal aristocracy nor the bourgeoisie, could solve the problem of putting an end to the backwardness of our country. More than that, not only were these classes unable to solve this problem, they were not even able to formulate the task in any satisfactory way. The age-old backwardness of our country can be ended only on the lines of successful socialist construction. And it can be ended only by the proletariat, which has established its dictatorship and has charge of the direction of the country.

It would be foolish to console ourselves with the thought that, since the backwardness of our country was not invented by us and was bequeathed to us by the whole history of our country, we cannot be, and do not have to be, responsible for it. That is not true, comrades. Since we have come to power and taken upon ourselves the task of transforming the country on the basis of socialism, we are responsible, and have to be responsible, for everything, the bad as well as the good. And just because we are responsible for everything, we must put an end to our technical and economic backwardness. We must do so without fail if we really want to overtake and outstrip the advanced capitalist countries. And only we Bolsheviks can do it. But precisely in order to accomplish this task, we must systematically achieve a fast rate of development of our industry. And that we are already achieving a fast rate of industrial development is now clear to everyone.

The question of overtaking and outstripping the advanced capitalist countries technically and economically is for us Bolsheviks neither new nor unexpected. It was raised in our country as early as in 1917, before the October Revolution. It was raised by Lenin as early as in September 1917, on the eve of the October Revolution, during the imperialist war, in his pamphlet The Impending Catastrophe and How to Combat It. Here is what Lenin said on this score:

"The result of the revolution has been that the political system of Russia has in a few months caught up with that of the advanced countries. But that is not enough. The war is inexorable; it puts the alternative with ruthless severity: either perish, or overtake and outstrip the advanced countries economically as well. . . . Perish or drive full-steam ahead. That is the alternative with which history has confronted us" (Vol. XXI, p. 191).

You see how bluntly Lenin put the question of ending our technical and economic backwardness.

Lenin wrote all this on the eve of the October Revolution, in the period before the proletariat had taken power, when the Bolsheviks had as yet neither state power, nor a socialised industry, nor a widely ramified co-operative network embracing millions of peasants, nor collective farms, nor state farms. Today, when we already have something substantial with which to end completely our technical and economic backwardness, we might paraphrase Lenin's words roughly as follows:

"We have overtaken and outstripped the advanced capitalist countries politically by establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat. But that is not enough. We must utilise the dictatorship of the proletariat, our socialised industry, transport, credit system, etc., the co-operatives, collective farms, state farms, etc., in order to overtake and outstrip the advanced capitalist countries economically as well."

The question of a fast rate of development of industry would not face us so acutely as it does now if we had such a highly developed industry and such a highly developed technology as Germany, say, and if the relative importance of industry in the entire national economy were as high in our country as it is in Germany, for example. If that were the case, we could develop our industry at a slower rate without fearing to fall behind the capitalist countries and knowing that we could outstrip them at one stroke. But then we should not be so seriously backward technically and economically as we are now. The whole point is that we are behind Germany in this respect and are still far from having overtaken her technically and economically.

The question of a fast rate of development of industry would not face us so acutely if we were not the only country but one of the countries of the dictatorship of the proletariat, if there were a proletarian dictatorship not only in our country but in other, more advanced countries as well, Germany and France, say.

If that were the case, the capitalist encirclement could not be so serious a danger as it is now, the question of the economic independence of our country would naturally recede into the background, we could integrate ourselves into the system of more developed proletarian states, we could receive from them machines for making our industry and agriculture more productive, supplying them in turn with raw materials and foodstuffs, and we could, consequently, expand our industry at a slower rate. But you know very well that that is not yet the case and that we are still the only country of the proletarian dictatorship and are surrounded by capitalist countries, many of which are far in advance of us technically and economically.

That is why Lenin raised the question of overtaking and outstripping the economically advanced countries as one of life and death for our development.

Such are the external conditions dictating a fast rate of development of our industry.

Internal conditions. But besides the external conditions, there are also internal conditions which dictate a fast rate of development of our industry as the main foundation of our entire national economy. I am referring to the extreme backwardness of our agriculture, of its technical and cultural level. I am referring to the existence in our country of an overwhelming preponderance of small commodity producers, with their scattered and utterly backward production, compared with which our large-scale socialist industry is like an island in the midst of the sea, an island whose base is expanding daily, but which is nevertheless an island in the midst of the sea.

We are in the habit of saying that industry is the main foundation of our entire national economy, including agriculture, that it is the key to the reconstruction of our backward and scattered system of agriculture on a collectivist basis. That is perfectly true. From that position we must not retreat for a single moment. But it must also be remembered that, while industry is the main foundation, agriculture constitutes the basis for industrial development, both as a market which absorbs the products of industry and as a supplier of raw materials and foodstuffs, as well as a source of the export reserves essential in order to import machinery for the needs of our national economy. Can we advance industry while leaving agriculture in a state of complete technical backwardness, without providing an agricultural base for industry, without reconstructing agriculture and bringing it up to the level of industry? No, we cannot.

Hence the task of supplying agriculture with the maximum amount of instruments and means of production essential in order to accelerate and promote its reconstruction on a new technical basis. But for the accomplishment of this task a fast rate of development of our industry is necessary. Of course, the reconstruction of a disunited and scattered agriculture is an incomparably more difficult matter than the reconstruction of a united and centralised socialist industry. But that is the task that confronts us, and we must accomplish it. And it cannot be accomplished except by a fast rate of industrial development.

We cannot go on indefinitely, that is, for too long a period, basing the Soviet regime and socialist construction on two different foundations, the foundation of the most large-scale and united socialist industry and the foundation of the most scattered and backward, small commodity economy of the peasants. We must gradually, but systematically and persistently, place our agriculture on a new technical basis, the basis of large-scale production, and bring it up to the level of socialist industry. Either we accomplish this task—in which case the final victory of socialism in our country will be assured, or we turn away from it and do not accomplish it—in which case a return to capitalism may become inevitable.

Here is what Lenin says on this score:

"As long as we live in a small-peasant country, there is a surer economic basis for capitalism in Russia than for communism. This must be borne in mind. Anyone who has carefully observed life in the countryside, as compared with life in the towns, knows that we have not torn out the roots of capitalism and have not undermined the foundation, the basis of the internal enemy. The latter depends on small-scale production, and there is only one way of undermining it, namely, to place the economy of the country, including agriculture, on a new technical basis, the technical basis of modern large-scale production. And it is only electricity that is such a basis. Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country" (Vol. XXVI, p. 46).

As you see, when Lenin speaks of the electrification of the country he means not the isolated construction of individual power stations, but the gradual "placing of the economy of the country, including agriculture,* on a new technical basis, the technical basis of modern large-scale production," which in one way or another, directly or indirectly, is connected with electrification.

Lenin delivered this speech at the Eighth Congress of Soviets in December 1920, on the very eve of the introduction of NEP, when he was substantiating the so-called plan of electrification, that is, the GOELRO plan. Some comrades argue on these grounds that the views expressed in this quotation have become inapplicable under present conditions. Why, we ask? Because, they say, much water has flown under the bridges since then. It is, of course, true that much water has flown under the bridges since then. We now have a developed socialist industry, we have collective farms on a mass scale, we have old and new state farms, we have a wide network of well-developed co-operative organisations, we have machine-hiring stations at the service of the peasant farms, we now practise the contract system as a new form of the bond, and we can put into operation all these and a number of other levers for gradually placing agriculture on a new technical basis. All this is true. But it is also true that, in spite of all this, we are still a small-peasant country where small-scale production predominates. And that is the fundamental thing. And as long as it continues to be the fundamental thing, Lenin's thesis remains valid that "as long as we live in a small-peasant country, there is a surer economic basis for capitalism in Russia than for communism," and that, consequently, the danger of the restoration of capitalism is no empty phrase.

Lenin says the same thing, but in a sharper form, in the plan of his pamphlet, The Tax in Kind, which was written after the introduction of NEP (March-April 1921):

"If we have electrification in 10-20 years, then the individualism of the small tiller, and freedom for him to trade locally are not a whit terrible. If we do not have electrification, a return to capitalism will be inevitable anyhow."

And further on he says:

"Ten or twenty years of correct relations with the peasantry, and victory on a world scale is assured (even if the proletarian revolutions, which are growing, are delayed); otherwise, 20-40 years of the torments of whiteguard terrorism" (Vol. XXVI, p. 313).

You see how bluntly Lenin puts the question: either electrification, that is, the "placing of the economy of the country, including agriculture, on a new technical basis, the technical basis of modern large-scale production," or a return to capitalism.

That is how Lenin understood the question of "correct relations with the peasantry."

It is not a matter of coddling the peasant and regarding this as establishing correct relations with him, for coddling will not carry you very far. It is a matter of helping the peasant to place his husbandry "on a new technical basis, the technical basis of modern large-scale production"; for that is the principal way to rid the peasant of his poverty.

And it is impossible to place the economy of the country on a new technical basis unless our industry and, in the first place, the production of means of production, are developed at a fast rate.

Such are the internal conditions dictating a fast rate of development of our industry.

It is these external and internal conditions which are the cause of the control figures of our national economy being under such tension.

That explains, too, why our economic plans, both budgetary and non-budgetary, are marked by a state of tension, by substantial investments in capital development, the object of which is to maintain a fast rate of industrial development.

It may be asked where this is said in the theses, in what passage of the theses. (A voice: "Yes, where is it said") Evidence of this in the theses is the sum-total of capital investments in industry for 1928-29. After all, our theses are called theses on the control figures. That is so, is it not, comrades? (A voice: "Yes.") Well, the theses say that in 1928-29 we shall be investing 1,650 million rubles in capital construction in industry. In other words, this year we shall be investing in industry 330,000,000 rubles more than last year.

It follows, therefore, that we are not only maintaining the rate of industrial development, but are going a step farther by investing more in industry than last year, that is, by expanding capital construction in industry both absolutely and relatively.

That is the crux of the theses on the control figures of the national economy. Yet certain comrades failed to observe this staring fact. They criticised the theses on the control figures right and left as regards petty details, but the most important thing they failed to observe.

II. The Grain Problem

I have spoken so far of the first main question in the theses, the rate of development of industry. Now let us consider the second main question, the grain problem. A characteristic feature of the theses is that they lay stress on the problem of the development of agriculture in general, and of grain farming in particular. Are the theses right in doing so? I think they are. Already at the July plenum it was said that the weakest spot in the development of our national economy is the excessive backwardness of agriculture in general, and of grain farming in particular.

When, in speaking of our agriculture lagging behind our industry, people complain about it, they are, of course, not talking seriously. Agriculture always has lagged and always: will lag behind industry. That is particularly true in our conditions, where industry is concentrated to a maximum degree, while agriculture is scattered to a maximum degree. Naturally, a united industry will develop faster than a scattered agriculture. That, incidently, gives rise to the leading position of industry in relation to agriculture. Consequently, the customary lag of agriculture behind industry does not give sufficient grounds for raising the grain problem.

The problem of agriculture, and of grain farming in particular, makes its appearance only when the customary lag of agriculture behind industry turns into an excessive lag in the rate of its development. The characteristic feature of the present state of our national economy is that we are faced by the fact of an excessive lag in the rate of development of grain farming behind the rate of development of industry, while at the same time the demand for marketable grain on the part of the growing towns and industrial areas is increasing by leaps and bounds. The task then is not to lower the rate of development of industry to the level of the development of grain farming (which would upset everything and reverse the course of development), but to bring the rate of development of grain farming into line with the rate of development of industry and to raise the rate of development of grain farming to a level that will guarantee rapid progress of the entire national economy, both industry and agriculture.

Either we accomplish this task, and thereby solve the grain problem, or we do not accomplish it, and then a rupture between the socialist town and the small-peasant countryside will be inevitable.

That is how the matter stands, comrades. That is the essence of the grain problem.

Does this not mean that what we have now is "stagnation" in the development of agriculture or even its "retrogression"? That is what Frumkin actually asserts in his second letter, which at his request we distributed today to the members of the C.C. and C.C.C. He says explicitly in this letter that there is "stagnation" in our agriculture. "We cannot and must not," he says, "talk in the press about retrogression, but within the Party we ought not to hide the fact that this lag is equivalent to retrogression."

Is this assertion of Frumkin's correct? It is, of course, incorrect! We, the members of the Political Bureau, absolutely disagree with this assertion, and the Political Bureau theses are totally at variance with such an opinion of the state of grain farming.

In point of fact, what is retrogression, and how would it manifest itself in agriculture? It would obviously be bound to manifest itself in a backward, downward movement of agriculture, a movement away from the new forms of farming to the old, medieval forms. It would be bound to manifest itself by the peasants abandoning, for instance, the three-field system for the long-fallow system, the steel plough and machines for the wooden plough, clean and selected seed for unsifted and low-grade seed, modern methods of farming for inferior methods, and so on and so forth. But do we observe anything of the kind? Does not everyone know that tens and hundreds of thousands of peasant farms are annually abandoning the three-field for the four-field and multi-field system, low-grade seed for selected seed, the wooden plough for the steel plough and machines, inferior methods of farming for superior methods? Is this retrogression?

Frumkin has a habit of hanging on to the coat tails of some member or other of the Political Bureau in order to substantiate his own point of view. It is quite likely that in this instance, too, he will get hold of Bukha-rin's coat tails in order to show that Bukharin in his article, "Notes of an Economist," says "the same thing." But what Bukharin says is very far from "the same thing." Bukharin in his article raised the abstract, theoretical question of the possibility or danger of retrogression. In the abstract, such a formulation of the question is quite possible and legitimate. But what does Frumkin do? He turns the abstract question of the possibility of the retrogression of agriculture into a fact. And this he calls an analysis of the state of grain farming! Is it not ludicrous, comrades?

It would be a fine Soviet government indeed if, in the eleventh year of its existence, it had brought agriculture into a state of retrogression! Why, a government like that would deserve not to be supported, but to be sent packing. And the workers would have sent such a government packing long ago, if it had reduced agriculture to a state of retrogression. Retrogression is a tune all sorts of bourgeois experts are harping on; they dream of our agriculture retrogressing. Trotsky at one time harped on the theme of retrogression. I did not expect to see Frumkin taking this dubious line.

On what does Frumkin base his assertion about retrogression? First of all, on the fact that the grain crop area this year is less than it was last year. What is this fact due to? To the policy of the Soviet Government, perhaps? Of course not. It is due to the perishing of the winter crops in the steppe area of the Ukraine and partially in the North Caucasus, and to the drought in the summer of this year in the same area of the Ukraine. Had it not been for these unfavourable weather conditions, upon which agriculture is wholly and entirely dependent, our grain crop area this year would have been at least 1,000,000 dessiatins larger than it was last year.

He bases his assertion, further, on the fact that our gross production of grain this year is only slightly (70,000,000 poods) greater, and that of wheat and rye 200,000,000 poods less, than last year. And what is all this due to? Again to the drought and to the frosts which killed the winter crops. Had it not been for these unfavourable weather conditions, our gross production of grain this year would have exceeded last year's by 300,000,000 poods. How can one ignore such factors as drought, frost, etc., which are of decisive significance for the harvest in this or that region?

We are now making it our task to enlarge the crop area by 7 per cent, to raise crop yields by 3 per cent, and to increase the gross production of grain by, I think, 10 per cent. There need be no doubt that we shall do-everything in our power to accomplish these tasks. But-in spite of all our measures, it is not out of the question that we may again come up against a partial crop failure, frosts or drought in this or that region, in which case it is possible that these circumstances may cause the gross grain output to fall short of our plans or even of this year's gross output. Will that mean that agriculture is "retrogressing," that the policy of the Soviet Government is to blame for this "retrogression," that we have "robbed" the peasant of economic incentive, that we have "deprived" him of economic prospects?

Several years ago Trotsky fell into the same error, declaring that "a little rain" was of no significance to agriculture. Rykov controverted him, and had the support of the overwhelming majority of the members of the C.C. Now Frumkin is falling into the same error, ignoring weather conditions, which are of decisive importance for agriculture, and trying to make the policy of our Party responsible for everything.

What ways and means are necessary to accelerate the rate of development of agriculture in general, and of grain farming in particular?

There are three such ways, or channels:

a) by increasing crop yields and enlarging the area sown by the individual poor and middle peasants;

b) by further development of collective farms;

c) by enlarging the old and establishing new state farms.

All this was already mentioned in the resolution of the July plenum. The theses repeat what was said at the July plenum, but put the matter more concretely, and state it in terms of figures in the shape of definite investments. Here, too, Frumkin finds something to cavil at. He thinks that, since individual farming is put in the first place and the collective farms and state farms in the second and third, this can only mean that his view-point has triumphed. That is ridiculous, comrades.

It is clear that if we approach the matter from the point of view of the relative importance of each form of agriculture, individual farming must be put in the first place, because it provides nearly six times as much marketable grain as the collective farms and state farms. But if we approach the matter from the point of view of the type of farming, of which form of economy is most akin to our purpose, first place must be given to the collective farms and state farms, which represent a higher type of agriculture than individual peasant farming. Is it really necessary to show that both points of view are equally acceptable to us?

What is required in order that our work should proceed along all these three channels, in order that the rate of development of agriculture, and primarily of grain farming, should be raised in practice?

It is necessary, first of all, to direct the attention of our Party cadres to agriculture and focus it on concrete aspects of the grain problem. We must put aside abstract phrases and talking about agriculture in general and get down, at last, to working out practical measures for the furtherance of grain farming adapted to the diverse conditions in the different areas. It is time to pass from words to deeds and to tackle at last the concrete question how to raise crop yields and to enlarge the crop areas of the individual poor- and middle-peasant farms, how to improve and develop further the collective farms and state farms, how to organise the rendering of assistance by the collective farms and state farms to the peasants by way of supplying them with better seed and better breeds of cattle, how to organise assistance for the peasants in the shape of machines and other implements through machine-hiring stations, how to extend and improve the contract system and agricultural co-operation in general, and so on and so forth. (A voice: "That is empiricism.") Such empiricism is absolutely essential, for otherwise we run the risk of drowning the very serious matter of solving the grain problem in empty talk about agriculture in general.

The Central Committee has set itself the task of arranging for concrete reports on agricultural development by our principal workers in the Council of People's Commissars and the Political Bureau who are responsible for the chief grain regions. At this plenum you are to hear a report by Comrade Andreyev on the ways of solving the grain problem in the North Caucasus. I think that we shall next have to hear similar reports in succession from the Ukraine, the Central Black Earth region, the Volga region, Siberia, etc. This is absolutely necessary in order to turn the Party's attention to the grain problem and to get our Party workers at last to formulate concretely the questions connected with the grain problem.

It is necessary, in the second place, to ensure that our Party workers in the countryside make a strict distinction in their practical work between the middle peasant and the kulak, do not lump them together and do not hit the middle peasant when it is the kulak that has to be struck at. It is high time to put a stop to these errors, if they may be called such. Take, for instance, the question of the individual tax. We have the decision of the Political Bureau, and the corresponding law, about levying an individual tax on not more than 2-3 per cent of the households, that is, on the wealthiest section of the kulaks. But what actually happens? There are a number of districts where 10, 12 and even more per cent of the households are taxed, with the result that the middle section of the peasantry is affected. Is it not time to put a stop to this crime?

Yet, instead of indicating concrete measures for putting a stop to these and similar outrages, our dear "critics" indulge in word play, proposing that the words "the wealthiest section of the kulaks" be replaced by the words "the most powerful section of the kulaks" or "the uppermost section of the kulaks." As if it were not one and the same thing! It has been shown that the kulaks constitute about 5 per cent of the peasantry. It has been shown that the law requires the individual tax to be levied on only 2-3 per cent of the households, that is, on the wealthiest section of the kulaks. It has been shown that in practice this law is being violated in a number of areas. Yet, instead of indicating concrete measures for putting a stop to this, the "critics" indulge in verbal criticism and refuse to understand that this does not alter things one iota. Sheer hair-splitters! (A voice: "They propose that the individual tax should be levied on all kulaks.") Well then, they should demand the repeal of the law imposing an individual tax on 2-3 per cent. Yet I have not heard that anybody has demanded the repeal of the individual tax law. It is said that individual taxation is arbitrarily extended in order to supplement the local budget. But you must not supplement the local budget by breaking the law, by infringing Party directives. Our Party exists, it has not been liquidated yet. The Soviet Government exists, it has not been liquidated yet. And if you have not enough funds for your local budget, then you must ask to have your local budget reconsidered, and not break the law or disregard Party instructions.

It is necessary, next, to give further incentives to individual poor- and middle-peasant farming. Undoubtedly, the increase in grain prices already introduced, practical enforcement of revolutionary law, practical assistance to the poor- and middle-peasant farms in the shape of the' contract system, and so on, will considerably increase the peasant's economic incentive. Frumkin thinks that we have killed or nearly killed the peasant's incentive by robbing him of economic prospects. That, of course, is nonsense. If it were true, it would be incomprehensible what the bond, the alliance between the working class and the main mass of the peasantry, actually rests on. It cannot be thought, surely, that this alliance rests on sentiment. It must be realised, after all, that the alliance between the working class and the peasantry is an alliance on a business basis, an alliance of the interests of two classes, a class alliance of the workers and the main mass of the peasantry aiming at mutual advantage. It is obvious that if we had killed or nearly killed the peasant's economic incentive by depriving him of economic prospects, there would be no bond, no alliance between the working class and the peasantry. Clearly, what is at issue here is not the "creation" or "release" of the economic incentive of the poor- and middle-peasant masses, but the strengthening and further development of this incentive, to the mutual advantage of the working class and the main mass of the peasantry. And that is precisely what the theses on the control figures of the national economy indicate.

It is necessary, lastly, to increase the supply of goods to the countryside. I have in mind both consumer goods and, especiaIly, production goods (machines, fertilisers, etc.) capable of increasing the output of agricultural produce. It cannot be said that everything in this respect is as it should be. You know that symptoms of a goods shortage are still far from having been eliminated, and will probably not be eliminated so soon. The illusion exists in certain Party circles that we can put an end to the goods shortage at once. That, unfortunately, is not true. It should be borne in mind that the symptoms of a goods shortage are connected, firstly, with the growing prosperity of the workers and peasants and the gigantic increase of effective demand for goods, production of which is growing year by year but which are not enough to satisfy the whole demand, and, secondly, with the present period of the reconstruction of industry.

The reconstruction of industry involves the transfer of funds from the sphere of producing means of consumption to the sphere of producing means of production. Without this there can be no serious reconstruction of industry, especially in our, Soviet conditions. But what does this mean? It means that money is being invested in the building of new plants, and that the number of towns and new consumers is growing, while the new plants can put out additional commodities in quantity only after three or four years. It is easy to realise that this is not conducive to putting an end to the goods shortage.

Does this mean that we must fold our arms and acknowledge that we are impotent to cope with the symptoms of a goods shortage? No, it does not. The fact is that we can and should adopt concrete measures to mitigate, to moderate the goods shortage. That is something we can and should do at once. For this, we must speed up the expansion of those branches of industry which directly contribute to the promotion of agricultural production (the Stalingrad Tractor Works, the Rostov Agricultural Machinery Works, the Voronezh Seed Sort-ter Factory, etc., etc.). For this, further, we must as far as possible expand those branches of industry which contribute to an increase in output of goods in short supply (cloth, glass, nails, etc.). And so on and so forth.

Kubyak said that the control figures of the national economy propose to assign less funds this year to individual peasant farming than last year. That, I think, is untrue. Kubyak apparently loses sight of the fact that this year we are giving the peasants credit under the contract system to the sum of about 300,000,000 rubles (nearly 100,000,000 more than last year). If this is taken into account, and it must be taken into account, it will be seen that this year we are assigning more for the development of individual peasant farming than last year. As to the old and new state farms and collective farms, we are investing in them this year about 300,000,000 rubles (some 150,000,000 more than last year).

Special attention needs to be paid to the collective farms, the state farms and the contract system. These things should not be regarded only as means of increasing our stocks of marketable grain. They are at the same time a new form of bond between the working class and the main mass of the peasantry.

Enough has already been said about the contract system and I shall not dwell upon it any further. Everyone realises that the application of this system on a mass scale makes it easier to unite the efforts of the individual peasant farms, introduces an element of permanency in the relations between the state and the peasantry, and so strengthens the bond between town and country.

I should like to draw your attention to the collective farms, and especially to the state farms, as levers which facilitate the reconstruction of agriculture on a new technical basis, causing a revolution in the minds of the peasants and helping them to shake off conservatism, routine. The appearance of tractors, large agricultural machines and tractor columns in our grain regions cannot but have its effect on the surrounding peasant farms. Assistance rendered the surrounding peasants in the way of seed, machines and tractors will undoubtedly be appreciated by the peasants and taken as a sign of the power and strength of the Soviet state, which is trying to lead them on to the high road of a substantial improvement of agriculture. We have not taken this circumstance into account until now and, perhaps, still do not sufficiently do so. But I think that this is the chief thing that the collective farms and state farms are contributing and could contribute at the present moment towards solving the grain problem and the strengthening of the bond in its new forms.

Such, in general, are the ways and means that we must adopt in our work of solving the grain problem.

III. Combating Deviations and Conciliation Towards Them

Let us pass now to the third main question of our theses, that of deviations from the Leninist line.

The social basis of the deviations is the fact that small-scale production predominates in our country, the fact that small-scale production gives rise to capitalist elements, the fact that our Party is surrounded by petty-bourgeois elemental forces, and, lastly, the fact that certain of our Party organisations have been infected by these elemental forces.

There, in the main, lies the social basis of the deviations.

All these deviations are of a petty-bourgeois character.

What is the Right deviation, which is the one chiefly in question here? In what direction does it tend to go? It tends towards adaptation to bourgeois ideology, towards adaptation of our policy to the tastes and requirements of the "Soviet" bourgeoisie.

What threat does the Right deviation hold out, if it should triumph in our Party? It would mean the ideological rout of our Party, a free rein for the capitalist elements, the growth of chances for the restoration of capitalism, or, as Lenin called it, for a "return to capitalism."

Where is the tendency towards a Right deviation chiefly lodged? In our Soviet, economic, co-operative and trade-union apparatuses, and in the Party apparatus as well, especially in its lower links in the countryside.

Are there spokesmen of the Right deviation among our Party members? There certainly are. Rykov mentioned the example of Shatunovsky, who declared against the building of the Dnieper Hydro-Electric Power Station. There can be no question but that Shatunovsky was guilty of a Right deviation, a deviation towards open opportunism. All the same, I think that Shatunovsky is not a typical illustration of the Right deviation, of its physiognomy. I think that in this respect the palm should go to Frumkin. (Laughter) I am referring to his first letter (June 1928) and then to his second letter, which was distributed here to the members of the C.C. and C.C.C. (November 1928). Let us examine both these letters. Let us take the "basic propositions" of the first letter.

1) "The sentiment in the countryside, apart from a small section of the poor peasants, is opposed to us." Is that true? It is obviously untrue. If it were true, the bond would not even be a memory. But since June (the letter was written in June) nearly six months have passed, yet anyone, unless he is blind, can see that the bond between the working class and the main mass of the peasantry continues and is growing stronger. Why does Frumkin write such nonsense? In order to scare the Party and make it give way to the Right deviation.

2) "The line taken lately has led to the main mass of the middle peasants being without hope, without prospects." Is that true? It is quite untrue. It is obvious that if in the spring of this year the main mass of the middle peasants had been without economic hope or prospects they would not have enlarged the spring crop area as they did in all the principal grain-growing regions. The spring sowing takes place in April-May. Well, Frumkin's letter was written in June. In our country, under the Soviet regime, who is the chief purchaser of cereals? The state and the co-operatives, which are linked with the state. It is obvious that if the mass of middle peasants had been without economic prospects, if they were in a state of "estrangement" from the Soviet Government, they would not have enlarged the spring crop area for the benefit of the state, as the principal purchaser of grain. Frumkin is talking obvious nonsense. Here again he is trying to scare the Party with the "horrors" of hopeless prospects in order to make it give way to his, Frumkin's, view.

3) "We must return to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Congresses." That the Fifteenth Congress has simply been tacked on here without rhyme or reason, of that there can be no doubt. The crux here is not in the Fifteenth Congress, but in the slogan: Back to the Fourteenth Congress. And what does that mean? It means renouncing "intensification of the offensive against the kulak" (see Fifteenth Congress resolution). I say this not in order to deprecate the Fourteenth Congress. I say it because, in calling for a return to the Fourteenth Congress, Frumkin is rejecting the step forward which the Party made between the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Congresses, and, in rejecting it, he is trying to pull the Party back. The July plenum of the Central Committee pronounced its opinion on this question. It stated plainly in its resolution that people who try to evade the Fifteenth Congress decision—"to develop further the offensive against the kulaks"—are "an expression of bourgeois tendencies in our country." I must tell Frumkin plainly that when the Political Bureau formulated this item of the resolution of the July plenum, it had him and his first letter in mind.

4) "Maximum assistance to the poor peasants entering collectives." We have always to the best of our ability and resources rendered the maximum assistance to the poor peasants entering, or even not entering, collectives. There is nothing new in this. What is new in the Fifteenth Congress decisions compared with those of the Fourteenth Congress is not this but that the Fifteenth Congress made the utmost development of the collective-farm movement one of the cardinal tasks of the day. When Frumkin speaks of maximum assistance to the poor peasants entering collectives, he is in point of fact turning away from, evading, the task set the Party by the Fifteenth Congress of developing the collective-farm movement to the utmost. In point of fact, Frumkin is against developing the work of strengthening the socialist sector in the countryside along the line of collective farms.

5) "State farms should not be expanded by shock or super-shock tactics." Frumkin cannot but know that we are only beginning to work seriously to expand the old state farms and to create new ones. Frumkin cannot but know that we are assigning for this purpose far less money than we ought to assign if we had any reserves for it. The words "by shock or super-shock tactics" were put in here to strike people with "horror" and to conceal his own disinclination for any serious expansion of the state farms. Frumkin, in point of fact, is here expressing his opposition to strengthening the socialist sector in the countryside along the line of the state farms.

Now gather all these propositions of Frumkin's together, and you get a bouquet characteristic of the Right deviation.

Let us pass to Frumkin's second letter. In what way does the second letter differ from the first? In that it aggravates the errors of the first letter. The first said that middle-peasant farming was without prospects. The second speaks of the "retrogression" of agriculture. The first letter said that we must return to the Fourteenth Congress in the sense of relaxing the offensive against the kulak. The second letter, however, says that "we must not hamper production on the kulak farms." The first letter said nothing about industry. But the second letter develops a "new" theory to the effect that less should be assigned for industrial construction. Incidentally, there are two points on which the two letters agree: concerning the collective farms and concerning the state farms. In both letters Frumkin pronounces against the development of collective farms and state farms. It is clear that the second letter aggravates the errors of the first.

About the theory of "retrogression" I have already spoken. There can be no doubt that this theory is the invention of bourgeois experts, who are always ready to raise a cry that the Soviet regime is doomed. Frumkin has allowed himself to be scared by the bourgeois experts who have their roost around the People's Commissariat of Finance, and now he is himself trying to scare the Party so as to make it give way to the Right deviation. Enough has been said, too, about the collective farms and state farms. So there is no need to repeat it. Let us examine the two remaining points: about kulak farming and about capital investment in industry.

Kulak farming. Frumkin says that "we must not hamper production on the kulak farms." What does that mean? It means not preventing the kulaks from developing their exploiting economy. But what does not preventing the kulaks from developing their exploiting economy mean? It means allowing a free rein to capitalism in the countryside, allowing it freedom, liberty. We get the old slogan of the French liberals: "laissez faire, laissez passer," that is, do not prevent the bourgeoisie from doing its business, do not prevent the bourgeoisie from moving freely.

This slogan was put forward by the old French liberals at the time of the French bourgeois revolution, at the time of the struggle against the feudal regime, which was fettering the bourgeoisie and not allowing it to develop. It follows, then, that we must now go over from the socialist slogan—"ever-increasing restrictions on the capitalist elements" (see the theses on the control figures)—to the bourgeois-liberal slogan: do not hamper the development of capitalism in the countryside. Why, are we really thinking of turning from Bolsheviks into bourgeois liberals? What can there be in common between this bourgeois-liberal slogan of Frumkin's and the line of the Party?

(Frumkin. "Comrade Stalin, read the other points also.") I shall read the whole point: "We must not hamper production on the kulak farms either, while at the same time combating their enslaving exploitation."

My dear Frumkin, do you really think the second part of the sentence improves matters and does not make them worse? What does combating enslaving exploitation mean? Why, the slogan of combating enslaving exploitation is a slogan of the bourgeois revolution, directed against feudal-serf or semi-feudal methods of exploitation. We did indeed put forward this slogan when we were advancing towards the bourgeois revolution, differentiating between the enslaving form of exploitation, which we were striving to abolish, and the non-enslaving, so-called "progressive" form of exploitation, which we could not at that time restrict or abolish, inasmuch as the bourgeois system remained in force. But at that time we were advancing towards a bourgeois-democratic republic. Now, however, if I am not mistaken, we have a socialist revolution, which is heading, and cannot but I head, for the abolition of all forms of exploitation, including "progressive" forms. Really, do you want us to turn back from the socialist revolution, which we are developing and advancing, and revert to the slogans of the bourgeois revolution? How can one bring oneself to talk such nonsense?

Further, what does not hampering kulak economy mean? It means giving the kulak a free hand. And what does giving the kulak a free hand mean? It means giving him power. When the French bourgeois liberals demanded that the feudal government should not hamper the development of the bourgeoisie, they expressed it concretely in the demand that the bourgeoisie should be given power. And they were right. In order to be able to develop properly, the bourgeoisie must have power. Consequently, to be consistent, you should say: admit the kulak to power. For it must be understood, after all, that you cannot but restrict the development of kulak economy if you take power away from the kulaks and concentrate it in the hands of the working class. Those are the conclusions that suggest themselves on reading Frumkin's second letter.

Capital construction in industry. When we discussed the control figures we had three figures before us: the Supreme Council of National Economy asked for 825,000,000 rubles; the State Planning Commission was willing to give 750,000,000 rubles; the People's Commissariat of Finance would give only 650,000,000 rubles. What decision on this did the Central Committee of our Party adopt? It fixed the figure at 800,000,000 rubles, that is, exactly 150,000,000 rubles more than the People's Commissariat of Finance proposed. That the People's Commissariat of Finance offered less is, of course, not surprising: the stinginess of the People's Commissariat of Finance is generally known; it has to be stingy. But that is not the point just now. The point is that Frumkin defends the figure of 650,000,000 rubles not out of stinginess, but because of his new-fangled theory of "feasibility," asserting in his second letter and in a special article in the periodical of the People's Commissariat of Finance that we shall certainly do injury to our economy if we assign to the Supreme Council of National Economy more than 650,000,000 rubles for capital construction. And what does that mean? It means that Frumkin is against maintaining the present rate of the development of industry, evidently failing to realise that if it were slackened this really would do injury to our entire national economy.

Now combine these two points in Frumkin's second letter, the point concerning kulak farming and the point concerning capital construction in industry, add the theory of "retrogression," and you get the physiognomy of the Right deviation.

You want to know what the Right deviation is and what it looks like? Read Frumkin's two letters, study them, and you will understand.

So much for the physiognomy of the Right deviation.

But the theses speak not only of the Right deviation. They speak also of the so-called "Left" deviation. What is the "Left" deviation? Is there really a so-called "Left" deviation in the Party? Are there in our Party, as our theses say, anti-middle-peasant trends, super-industrialisation trends and so on? Yes, there are. What do they amount to? They amount to a deviation towards Trotskyism. That was said already by the July plenum. I am referring to the July plenum's resolution on grain procurement policy, which speaks of a struggle on two fronts: against those who want to hark back from the Fifteenth Congress—the Rights, and against those who want to convert the emergency measures into a permanent policy of the Party—the "Lefts," the trend towards Trotskyism.

Clearly, there are elements of Trotskyism and a trend towards the Trotskyist ideology within our Party. About four thousand persons, I think, voted against our platform during the discussion which preceded the Fifteenth Party Congress. (A voice: "Ten thousand.") I think that if ten thousand voted against, then twice ten thousand Party members who sympathise with Trotskyism did not vote at all, because they did not attend the meetings. These are the Trotskyist elements who have not left the Party, and who, it must be supposed, have not yet rid themselves of the Trotskyist ideology. Furthermore, I think that a section of the Trotskyists who later broke away from the Trotskyist organisation and returned to the Party have not yet succeeded in shaking off the Trotskyist ideology and are also, presumably, not averse to disseminating their views among Party members. Lastly, there is the fact that we have a certain recrudescence of the Trotskyist ideology in some of our Party organisations. Combine all this, and you get all the necessary elements for a deviation towards Trotskyism in the Party.

And that is understandable: with the existence of petty-bourgeois elemental forces, and the pressure that these forces exert on our Party, there cannot but be Trotskyist trends in it. It is one thing to arrest Trotskyist cadres or expel them from the Party. It is another thing to put an end to the Trotskyist ideology. That will be more difficult. And we say that wherever there is a Right deviation, there is bound to be also a "Left" deviation. The "Left" deviation is the shadow of the Right deviation. Lenin used to say, referring to the Otzovists, that the "Lefts" are Mensheviks, only turned inside-out. That is quite true. The same thing must be said of the present "Lefts." People who deviate towards Trotskyism are in fact also Rights, only turned inside-out, Rights who cloak themselves with "Left" phrases.

Hence the fight on two fronts—both against the Right deviation and against the "Left" deviation.

It may be said: if the "Left" deviation is in essence the same thing as the Right opportunist deviation, then what is the difference between them, and where do you actually get two fronts? Indeed, if a victory of the Rights means increasing the chances of the restoration of capitalism, and a victory of the "Lefts" would lead to the same result, what difference is there between them, and why are some called Rights and others "Lefts"? And if there is a difference between them, what is it? Is it not true that the two deviations have the same social roots, that they are both petty-bourgeois deviations? Is it not true that both these deviations, if they were to triumph, would lead to one and the same result? What, then, is the difference between them?

The difference is in their platforms, their demands, their approach and their methods.

If, for example, the Rights say: "It was a mistake to build the Dnieper Hydro-Electric Power Station," and the "Lefts," on the contrary, declare: "What is the use of one Dnieper Hydro-Electric Power Station, let us have a Dnieper Hydro-Electric Power Station every year" (laughter) , it must be admitted that there obviously is a difference.

If the Rights say: "Let the kulak alone, allow him to develop freely," and the "Lefts," on the contrary, declare: "Strike not only at the kulak, but also at the middle peasant, because he is just as much a private owner as the kulak," it must be admitted that there obviously is a difference.

If the Rights say: "Difficulties have arisen, is it not time to quit?" and the "Lefts," on the contrary, declare: "What are difficulties to us, a fig for your difficulties—full speed ahead!" (laughter), it must be admitted that there obviously is a difference.

There you have a picture of the specific platform and the specific methods of the "Lefts." This, in fact, explains why the "Lefts" sometimes succeed in luring a part of the workers over to their side with the help of high-sounding "Left" phrases and by posing as the most determined opponents of the Rights, although all the world knows that they, the "Lefts," have the same social roots as the Rights, and that they not infrequently join in an agreement, a bloc, with the Rights in order to fight the Leninist line.

That is why it is obligatory for us, Leninists, to wage a fight on two fronts—both against the Right deviation and against the "Left" deviation.

But if the Trotskyist trend represents a "Left" deviation, does not this mean that the "Lefts" are more to the Left than Leninism? No, it does not. Leninism is the most Left (without quotation marks) trend in the world labour movement. We Leninists belonged to the Second International down to the outbreak of the imperialist war as the extreme Left group of the Social-Democrats. We did not remain in the Second International and we advocated a split in the Second International precisely because, being the extreme Left group, we did not want to be in the same party as the petty-bourgeois traitors to Marxism, the social-pacifists and social-chauvinists.

It was these tactics and this ideology that subsequently became the basis of all the Bolshevik parties of the world. In our Party, we Leninists are the sole Lefts without quotation marks. Consequently, we Leninists are neither "Lefts" nor Rights in our own Party. We are a party of Marxist-Leninists. And within our Party we combat not only those whom we call openly opportunist deviators, but also those who pretend to be "Lefter" than Marxism, "Lefter" than Leninism, and who camouflage their Right, opportunist nature with high-sounding "Left" phrases.

Everybody realises that when people who have not yet rid themselves of Trotskyist trends are called "Lefts," it is meant ironically. Lenin referred to the "Left Communists" as Lefts sometimes with and sometimes without quotation marks. But everyone realises that Lenin called them Lefts ironically, thereby emphasising that they were Lefts only in words, in appearance, but that in reality they represented petty-bourgeois Right trends.

In what possible sense can the Trotskyist elements be called Lefts (without quotation marks), if only yesterday they joined in a united anti-Leninist bloc with openly opportunist elements and linked themselves directly and immediately with the anti-Soviet strata of the country? Is it not a fact that only yesterday we had an open bloc of the "Lefts" and the Rights against the Leninist Party, and that that bloc undoubtedly had the support of the bourgeois elements? And does not this show that they, the "Lefts" and the Rights, could not have joined together in a united bloc if they did not have common social roots, if they were not of a common opportunist nature? The Trotskyist bloc fell to pieces a year ago. Some of the Rights, such as Shatu-novsky, left the bloc. Consequently, the Right members of the bloc will now come forward as Rights, while the "Lefts" will camouflage their Rightism with "Left" phrases. But what guarantee is there that the "Lefts" and the Rights will not find each other again? (Laughter.) Obviously, there is not, and cannot be, any guarantee of that. But if we uphold the slogan of a fight on two fronts, does this mean that we are proclaiming the necessity of Centrism in our Party? What does a fight on two fronts mean? Is this not Centrism? You know that that is exactly how the Trotskyists depict matters: there are the "Lefts," that is, "we," the Trotskyists, the "real Leninists"; there are the "Rights," that is, all the rest; and, lastly, there are the "Centrists," who vacillate between the "Lefts" and the Rights. Can that be considered a correct view of our Party? Obviously not. Only people who have become confused in all their concepts and who have long ago broken with Marxism can say that. It can be said only by people who fail to see and to understand the difference in principle between the Social-Democratic party of the pre-war period, which was the party of a bloc of proletarian and petty-bourgeois interests, and the Communist Party, which is the monolithic party of the revolutionary proletariat.

Centrism must not be regarded as a spatial concept: the Rights, say, sitting on one side, the "Lefts" on the other, and the Centrists in between. Centrism is a political concept. Its ideology is one of adaptation, of subordination of the interests of the proletariat to the interests of the petty bourgeoisie within one common party. This ideology is alien and abhorrent to Leninism.

Centrism was a phenomenon that was natural in the Second International of the period before the war. There were Rights (the majority), Lefts (without quotation marks), and Centrists, whose whole policy consisted in embellishing the opportunism of the Rights with Left phrases and subordinating the Lefts to the Rights.

What, at that time, was the policy of the Lefts, of whom the Bolsheviks constituted the core? It was one of determinedly fighting the Centrists, of fighting for a split with the Rights (especially after the outbreak of the imperialist war) and of organising a new, revolutionary International consisting of genuinely Left, genuinely proletarian elements.

Why was it possible that there could arise at that time such an alignment of forces within the Second International and such a policy of the Bolsheviks within it? Because the Second International was at that time the party of a bloc of proletarian and petty-bourgeois interests serving the interests of the petty-bourgeois social-pacifists, social-chauvinists. Because the Bolsheviks could not at that time but concentrate their fire on the Centrists, who were trying to subordinate the proletarian elements to the interests of the petty bourgeoisie. Because the Bolsheviks were obliged at that time to advocate the idea of a split, for otherwise the proletarians could not have organised their own monolithic revolutionary Marxist party.

Can it be asserted that there is a similar alignment of forces in our Communist Party, and that the same policy must be practised in it as was practised by the Bolsheviks in the parties of the Second International of the period before the war? Obviously not. It cannot, because it would signify a failure to understand the difference in principle between Social-Democracy, as the party of a bloc of proletarian and petty-bourgeois elements, and the monolithic Communist Party of the revolutionary proletariat. They (the Social-Democrats) had one underlying class basis for the party. We (the Communists) have an entirely different underlying basis. With them (the Social-Democrats) Centrism was a natural phenomenon, because the party of a bloc of heterogeneous interests cannot get along without Centrists, and the Bolsheviks were obliged to work for a split. With us (the Communists) Centrism is purposeless and incompatible with the Leninist Party principle, since the Communist Party is the monolithic party of the proletariat, and not the party of a bloc of heterogeneous class elements.

And since the prevailing force in our Party is the most Left of the trends in the world labour movement (the Leninists), a splitting policy in our Party has not and cannot have any justification from the standpoint of Leninism. (A voice: "Is a split possible in our Party, or not?") The point is not whether a split is possible; the point is that a splitting policy in our monolithic Leninist Party cannot be justified from the standpoint of Leninism.

Whoever fails to understand this difference in principle is going against Leninism and is breaking with Leninism.

That is why I think that only people who have taken leave of their senses and have lost every shred of Marxism can seriously assert that the policy of our Party, the policy of waging a fight on two fronts, is a Centrist policy.

Lenin always waged a fight on two fronts in our Party—both against the "Lefts" and against outright Menshevik deviations. Study Lenin's pamphlet, "Left-Wing" Communism, an Infantile Disorder, study the history of our Party, and you will realise that our Party grew and gained strength in a struggle against both de-viations—the Right and the "Left." The fight against the Otzovists and the "Left" Communists, on the one hand, and the fight against the openly opportunist deviation before, during and after the October Revolution, on the other hand—such were the phases that our Party passed through in its development. Everyone is familiar with the words of Lenin that we must wage a fight both against open opportunists and against "Left" doctrinaires.

Does this mean that Lenin was a Centrist, that he pursued a Centrist policy? It obviously does not.

That being the case, what do our Right and "Left" deviators represent?

As to the Right deviation, it is not, of course, the opportunism of the pre-war Social-Democrats. A deviation towards opportunism is not yet opportunism. We are familiar with the explanation Lenin gave of the concept of deviation. A deviation to the Right is something which has not yet taken the shape of opportunism and which can be corrected. Consequently, a deviation to the Right must not be identified with out-and-out opportunism.

As to the "Left" deviation, it is something diametrically opposite to what the extreme Lefts in the prewar Second International, that is, the Bolsheviks, represented. Not only are the "Left" deviators not Lefts without quotation marks, they are essentially Right deviators, with the difference, however, that they unconsciously camouflage their true nature by means of "Left" phrases. It would be a crime against the Party not to perceive the vast difference between the "Left" deviators and genuine Leninists, who are the only Lefts (without quotation marks) in our Party. (A voice: "What about the legalisation of deviations?") If waging an open fight against deviations is legalisation, then it must be confessed that Lenin "legalised" them long ago.

These deviators, both Rights and "Lefts," are recruited from the most diverse elements of the non-proletarian strata, elements who reflect the pressure of the petty-bourgeois elemental forces on the Party and the degeneration of certain sections of the Party. Former members of other parties; people in the Party with Trotskyist trends; remnants of former groups in the Party; Party members in the state, economic, cooperative and trade-union apparatuses who are becoming (or have become) bureaucratised and are linking themselves with the outright bourgeois elements in these apparatuses; well-to-do Party members in our rural organisations who are merging with the kulaks, and so on and so forth—such is the nutritive medium for deviations from the Leninist line. It is obvious that these elements are incapable of absorbing anything genuinely Left and Leninist. They are only capable of nourishing the openly opportunist deviation, or the so-called "Left" deviation, which masks its opportunism with Left phrases.

That is why a fight on two fronts is the only correct policy for the Party.

Further. Are the theses correct in saying that our chief method of fighting the Right deviation should be that of a full-scale ideological struggle? I think they are. It would be well to recall the experience of the fight against Trotskyism. With what did we begin the fight against Trotskyism? Was it, perhaps, with organisational penalties? Of course not! We began it with an ideological struggle. We waged it from 1918 to 1925. Already in 1924 our Party and the Fifth Congress of the Comintern passed a resolution on Trotskyism defining it as a petty-bourgeois deviation. Nevertheless, Trotsky continued to be a member of our Central Committee and Political Bureau. Is that a fact, or not? It is a fact. Consequently, we "tolerated" Trotsky and the Trotsky-ists on the Central Committee. Why did we allow them to remain in leading Party bodies? Because at that time the Trotskyists, despite their disagreements with the Party, obeyed the decisions of the Central Committee and remained loyal. When did we begin to apply organisational penalties at all extensively? Only after the Trotskyists had organised themselves into a faction, set up their factional centre, turned their faction into a new party and began to summon people to anti-Soviet demonstrations.

I think that we must pursue the same course in the fight against the Right deviation. The Right deviation cannot as yet be regarded as something which has taken definite shape and crystallised, although it is gaining ground in the Party. It is only in process of taking shape and crystallising. Do the Right deviators have a faction? I do not think so. Can it be said that they do not submit to the decisions of our Party? I think we have no grounds yet for accusing them of this. Can it be affirmed that the Right deviators will certainly organise themselves into a faction? I doubt it. Hence the conclusion that our chief method of fighting the Right deviation at this stage should be that of a full-scale ideological struggle. This is all the more correct as there is an opposite tendency among some of the members of our Party— a tendency to begin the fight against the Right deviation not with an ideological struggle, but with organisational penalties. They say bluntly: Give us ten or twenty of these Rights and we'll make mincemeat of them in a trice and so put an end to the Right deviation. I think, comrades, that such sentiments are wrong and dangerous. Precisely in order to avoid being carried away by such sentiments, and in order to put the fight against the Right deviation on correct lines, it must be said plainly and resolutely that our chief method of fighting the Right deviation at this stage is an ideological struggle.

Does that mean that we rule out all organisational penalties? No, it does not. But it does undoubtedly mean that organisational penalties must play a subordinate role, and if there are no instances of infringement of Party decisions by Right deviators, we must not expel them from leading organisations or institutions. (A voice: "What about the Moscow experience?")

I do not think that there were any Rights among the leading Moscow comrades. There was in Moscow an incorrect attitude towards Right sentiments. More accurately, it could be said that there was a conciliatory tendency there. But I cannot say that there was a Right deviation in the Moscow Committee. (A voice: "But was there an organisational struggle?")

There was an organisational struggle, although it played a minor role. There was such a struggle because new elections are being held in Moscow on the basis of self-criticism, and district meetings of actives have the right to replace their secretaries. (Laughter.) (A voice: "Were new elections of our secretaries announced?") Nobody has forbidden new elections of secretaries. There is the June appeal of the Central Committee, which expressly says that development of self-criticism may become an empty phrase if the lower organisations are not assured the right to replace any secretary, or any committee. What objection can you raise to such an appeal? (A voice: "Before the Party Conference?") Yes, even before the Party Conference.

I see an incredulous smile on the faces of some comrades. That will not do, comrades. I see that some of you have an irrepressible desire to remove certain spokesmen of the Right deviation from their posts as quickly as possible. But that, dear comrades, is no solution of the problem. Of course, it is easier to remove people from their posts than to conduct a broad and intelligent campaign explaining the Right deviation, the Right danger, and how to combat it. But what is easiest must not be considered the best. Be so good as to organise a broad explanatory campaign against the Right danger, be so good as not to grudge the time for it, and then you will see that the broader and deeper the campaign, the worse it will be for the Right deviation. That is why I think that the central point of our fight against the Right deviation must be an ideological struggle.

As to the Moscow Committee, I do not know that anything can be added to what Uglanov said in his reply to the discussion at the plenum of the Moscow Committee and Moscow Control Commission of the C.P.S.U.(B.). He said plainly:

"If we recall a little history, if we recall how I fought Zinoviev in Leningrad in 1921, it will be seen that at that time the ‘affray' was somewhat fiercer. We were the victors then because we were in the right. We have been beaten now because we are in the wrong. It will be a good lesson."

It follows that Uglanov has been waging a fight now just as at one time he waged a fight against Zinoviev. Against whom, may it be asked, has he been waging his present fight? Evidently, against the policy of the C.C. Against whom else could he have waged it? On what basis could he have waged this fight? Obviously, on the basis of conciliation towards the Right deviation.

The theses, therefore, quite rightly stress, as one of the immediate tasks of our Party, the necessity of waging a fight against conciliation towards deviations from the Leninist line, especially against conciliation towards the Right deviation.

Finally, a last point. The theses say that we must particularly stress the necessity at this time of fighting the Right deviation. What does that mean? It means that at this moment the Right danger is the chief danger in our Party. A fight against Trotskyist trends, and a concentrated fight at that, has been going on already for some ten years. This fight has resulted in the rout of the main Trotskyist cadres. It cannot be said that the fight against the openly opportunist trend has been waged of late with equal intensity. It has not been waged with special intensity because the Right deviation is still in a period of formation and crystallisation, growing and gaining strength because of the strengthening of the petty-bourgeois elemental forces, which have been fostered by our grain procurement difficulties. The chief blow must therefore be aimed at the Right deviation.

In conclusion, I should like, comrades, to mention one more fact, which has not been mentioned here and which, in my opinion, is of no little significance. We, the members of the Political Bureau, have laid before you our theses on the control figures. In my speech, I upheld these theses as unquestionably correct. I do not say that certain corrections may not be made in the theses. But that they are in the main correct and assure the proper carrying out of the Leninist line, of that there can be no doubt whatever. Well, I must tell you that we in the Political Bureau adopted these theses unanimously. I think that this fact is of some significance in view of the rumours which are now and again spread in our ranks by diverse ill-wishers, opponents and enemies of our Party. I have in mind the rumours to the effect that in the Political Bureau we have a Right deviation, a "Left" deviation, conciliation and the devil knows what besides. Let these theses serve as one more proof, the hundredth or hundred and first, that we in the Political Bureau are all united.

I should like this plenum to adopt these theses, in principle, with equal unanimity. (Applause.)

Pravda, No. 273, November 24, 1928

Notes