Library:Interview with Marta Harnecker

Interview with Marta Harnecker | |

|---|---|

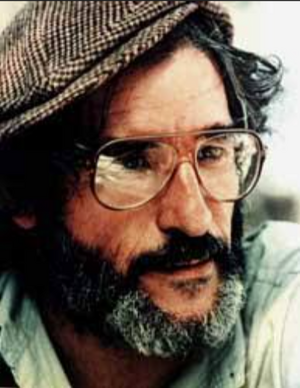

Manuel Pérez, author. | |

| Written by | Manuel Pérez |

| Written in | 1987 |

| Source | Memoirs - Manuel Pérez Martínez |

Interview with Marta Harnecker

1987

M. Harnecker: Manuel, since you are a priest and the top leader of UCELN, how do you assess the contribution of Christians to the revolution?

Manuel: It is very important for the revolution and for Christians. It is the way to effectively love the poor and contribute to the participation of all the people in the revolution. In a believing and exploited continent, the great diabolical stigma that the revolution was carried out only by atheists, and that these were wicked people, has been broken. This greatly helps all the people to participate in the revolution, because their belief and faith, instead of preventing them from participating, encourages and stimulates them in their revolutionary commitment. This, in turn, allows the Church itself, like the rest of society, to be permeated by the class struggle, thus breaking the pattern of resignation.

It is the revolutionary Christianity inherent in the Latin American identity, the practice and testimony of Camilo and thousands of Christians, that has contributed to the development of Liberation Theology, which is the reading of the Gospel from the perspective of the oppressed majorities. But I want to emphasize three central points of the contribution of Christians to the revolution.

First, Christianity places great emphasis on the human person as the subject of the revolution and, therefore, imbues the struggle with humanism.

Second, it insists on the direct participation of the individual in the construction of their own destiny, which helps make democracy more direct and allows the people to participate more directly in the construction and exercise of power.

Third, it generates forms of organization such as the base ecclesial communities which, while pluralistic, have a markedly popular character and are open to political commitment.

MH: How do you reconcile Marxism and Christianity?

Manuel: From the beginning, the ELN (National Liberation Army) based its actions more on common political practice and a clear commitment to social transformation than on engaging in extensive theoretical and philosophical debates to justify its identity. On the other hand, in recent years, Marxism has been undertaking theoretical work on Latin America that acknowledges the revolutionary potential of popular Christianity, and in turn, revolutionary Christianity has been increasingly incorporating elements of Marxism, which have influenced the development of a very unique Liberation Theology for Latin America.

This debate and mutual enrichment, stemming from the theoretical contradictions that arise from a shared practice—where there are political identities but differences in some motivations and philosophical tenets—has not concluded, but rather remains a constant source of new inquiries and theoretical developments.

MH: Is it effective for you to declare yourself a Marxist before a Christian?

Manuel: Look, Marta, according to my initial formation as a committed Christian, immersed in a social and popular reality, and my 20 years of political participation in what is now the UCELN, I have gained a political-ideological identity that is that of the Organization, in whose construction of revolutionary thought I feel I participate.

From that point of view, I feel identified with the Marxist ideological guidance that the Organization embodies, which does not prevent but rather allows and encourages the participation of Christians in it. I have always felt like a bridge of unity between comrades who, coming from a Marxist theoretical background or from a motivation of faith for their initial commitment, find a political identity in the UC-ELN.

It is undeniable that the science for the revolution is Marxism-Leninism, and that is accepted by all the Christians participating in the Organization. As a leader, then, I feel fully committed to the construction of the revolution in its global project, which leads me not to actively appeal to my Christian origin for revolutionary commitment.

MH: Manuel, I understand that you participated directly in those execution processes. How did you view that phenomenon as a Christian and a priest?

Manuel: Because of my background, the phenomenon was hard and painful for me and led me to profound reflections. Likewise, I saw many other comrades suffer.

For example, Manuel Vázquez Castaño left a meeting one day crying, a meeting in which, according to the codes, the execution of two comrades had to be decided.

This, logically, has led me to participate, along with other comrades, in the process of eliminating the multiple causes that made this practice unavoidable. For example: establishing criteria for joining the guerrilla movement, transforming codes and methods for determining punishments and sanctions, creating conditions so that social crimes can be addressed in ways that allow for the rehabilitation of individuals, etc.

MH: What lessons can be learned from this for the revolutionary movement?

Manuel: Among the lessons, we could list the following:

First, keep in mind that the humanization of the revolution is an essential element, which develops gradually, but which is always the ideal.

Initially, organizations are very vulnerable to being wiped out and therefore prioritize internal defense, but little by little, they make this humanism more real, until the greatest challenge becomes the greater dignification of life.

Second, I believe that public self-criticism by revolutionary organizations is the best way to transform and rectify historical mistakes.

Third, it is fundamental to consider the dignity and value of the individual human being, striving to maintain a perfect balance with their collective value, so as not to turn these aspects into absolute values that lead to extremes.