Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

| Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Союз Советских Социалистических Республик | |

|---|---|

| 1922–1991 | |

|

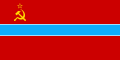

Flag

(1936–1955) | |

|

Motto: Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь! | |

|

Anthem: Государственный гимн СССР ("State Anthem of the Soviet Union") | |

| |

| Capital and largest city |

Moscow |

| Official languages |

None (1922–1990) Russian (1990–1991) |

| Mode of production |

Socialism (1928–1955) Capitalism (1956–1991) |

| Government | Federal Marxist–Leninist Soviet socialist republic (until 1956) |

• Notable leaderships |

Vladimir Lenin (1922–1924) Joseph Stalin (1924–1953) |

| History | |

| 1917 November 7th | |

| 1922 December 30th | |

• World War II victory |

1945 May 9th |

• Counter-revolution |

1953–1957 |

| 1991 December 26th | |

| Population | |

• 1989 estimate |

285,742,511[1] |

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR),[a] also known as the Soviet Union[b] was a transcontinental socialist state that existed from 1922 until its dissolution in 1991. It was founded in 1922 following the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917 and was the first state to achieve socialism.

The Soviet Union was a federal state composed for much of existence of fifteen separate Union Republics, all of which existed on a voluntary and equal basis within the Union. Through workers' and peasants' councils and the party, the Soviet Union formed and consolidated as a major socialist state under a dictatorship of the proletariat. Having begun its socialist construction under the leadership of Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s with the discontinuation of the New Economic Policy, the Soviet Union withstood periods of capitalist encirclement and aggression along with internal reaction resulting from collectivization, defending itself and aiding other revolutionary movement abroad, particularly after the Second World War.

After its victory in 1945 against fascism, the Soviet Union and people's democracies of Eastern Europe would enter into a new prolonged period of tension with the Western imperialist powers often known as the Cold War. It was in this time when the Soviet Union experienced a revisionist counter-revolution led by the clique of Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev and his successors would begin the restoration of capitalism and dismantlement of the workers' state in 1956. These regressions would culminate with the dissolution of the Union itself in 1991 under the tenure of anti-communist leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

History

Background

Russian Empire

In 1861, the Russian Empire, also known as Tsarist Russia, abolished serfdom. However, the situation for peasants "remained almost the same as it had been under serfdom, the only difference being that the peasant was now personally free, could not be bought and sold like a chattel."[5] These conditions led to the labor movement in Russia growing, as capitalism had recently been established. In 1903, the Russian Social–Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) was formed. However, a counter-revolutionary trend began to arise in the RSDLP.

This trend was known as Menshevism, and was led by Julius Martov.

According to Lenin's formulation, one could be a member of the Party who accepted its program, supported it financially, and belonged to one of its organizations. Martov's formulation, while admitting that acceptance of the program and financial support of the Party were indispensable conditions of Party membership, did not, however, make it a condition that a Party member should belong to one of the Party organizations, maintaining that a Party member need not necessarily belong to a Party organization.

Lenin regarded the Party as an organized detachment, whose members cannot just enroll themselves in the Party, but must be admitted into the Party by one of its organizations, and hence must submit to Party discipline. Martov, on the other hand, regarded the Party as something organizationally amorphous, whose members enroll themselves in the Party and are therefore not obliged to submit to Party discipline, inasmuch as they do not belong to a Party organization.

Thus, unlike Lenin's formulation, Martov's formulation would throw the door of the Party wide open to unstable non-proletarian elements. On the eve of the bourgeois-democratic revolution there were people among the bourgeois intelligentsia who for a while sympathized with the revolution. From time to time they might even render some small service to the Party. But such people would not join an organization, submit to Party discipline, carry out Party tasks and run the accompanying risks. Yet Martov and the other Mensheviks proposed to regard such people as Party members, and to accord them the right and opportunity to influence Party affairs.[5]

…as we proceed with the building of a real party, the class-conscious worker must learn to distinguish the mentality of the soldier of the proletarian army from the mentality of the bourgeois intellectual who parades anarchistic phrases; he must learn to insist that the duties of a Party member be fulfilled not only by the rank and file, but by the “people at the top” as well; he must learn to treat tail-ism in matters of organisation with the same contempt as he used, in days gone by, to treat tail-ism in matters of tactics![6]

In 1903, the Mensheviks showed their capacity for splitting behavior by using the newspaper for it:

On Lenin's proposal, Lenin, Plekhanov and Martov were elected to the editorial board of Iskra. Martov had demanded the election of all the six former members of the Iskra editorial board, the majority of whom were Martov's followers. This demand was rejected by the majority of the congress. The three proposed by Lenin were elected. Martov thereupon announced that he would not join the editorial board of the central organ.[5]

In 1905, a bourgeois revolution swept in Russia, and the Tsar, afraid for his autocracy, wrote a manifesto claiming that he supported basic "democratic" rights. This quelled the masses a bit, but still many did not believe his lies.

Lenin regarded the Manifesto of October 17 as an expression of a certain temporary equilibrium of forces: the proletariat and the peasantry, having wrung the Manifesto from the tsar, were still not strong enough to overthrow tsardom, whereas tsardom was no longer able to rule by the old methods alone and had been compelled to give a paper promise of "civil liberties" and a "legislative" Duma.[5]

However, the revolution died down, and the abolition of tsardom still did not occur. This was until, of course, Russia entered an imperialist war with Germany.

On July 14 (27, New Style), 1914, the tsarist government proclaimed a general mobilization. On July 19 (August 1, New Style) Germany declared war on Russia.

Russia entered the war.

Long before the actual outbreak of the war the Bolsheviks, headed by Lenin, had foreseen that it was inevitable. At international Socialist congresses Lenin had put forward proposals the purpose of which was to determine a revolutionary line of conduct for the Socialists in the event of war.

Lenin had pointed out that war is an inevitable concomitant of capitalism. Plunder of foreign territory, seizure and spoliation of colonies and the capture of new markets had many times already served as causes of wars of conquest waged by capitalist states. For capitalist countries war is just as natural and legitimate a condition of things as the exploitation of the working class.

Wars became inevitable particularly when, at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, capitalism definitely entered the highest and last stage of its development—imperialism. Under imperialism the powerful capitalist associations (monopolies) and the banks acquired a dominant position in the life of the capitalist states. Finance capital became master in the capitalist states. Finance capital demanded new markets, the seizure of new colonies, new fields for the export of capital, new sources of raw material.[5]

The growing anger about the war and distrust of the Tsarists led to the February Bourgeois–Democratic Revolution, establishing the provisional government.

Provisional Government

In 12 March 1917, the provisional government was formed. The workers originally held high confidence in it, but this began to wane when the provisional government did not end the war.

While the workers and peasants who were shedding their blood making the revolution expected that the war would be terminated, while they were fighting for bread and land and demanding vigorous measures to end the economic chaos, the Provisional Government remained deaf to these vital demands of the people. Consisting as it did of prominent representatives of the capitalists and landlords, this government had no intention of satisfying the demand of the peasants that the land be turned over to them. Nor could they provide bread for the working people, because to do so they would have to encroach on the interests of the big grain dealers and to take grain from the landlords and the kulaks by every available means; and this the government did not dare to do, for it was itself tied up with the interests of these classes. Nor could it give the people peace. Bound as it was to the British and French imperialists, the Provisional Government had no intention of terminating the war; on the contrary, it endeavoured to take advantage of the revolution to make Russia's participation in the imperialist war even more active, and to realize its imperialist designs of seizing Constantinople, the Straits and Galicia. It was clear that the people's confidence in the policy of the Provisional Government must soon come to an end.[5]

And it did. The demonstration of 4 July fought against the bourgeois democrats and campaigned for the end of the war. However, the counter-revolutionary provisional government massacred the peaceful demonstrators of the revolution. At the same time, they put out an arrest warrant on Lenin and raided the offices of Pravda, killing one person.

The Pravda premises were wrecked. Pravda, Soldatskaya Pravda (Soldiers' Truth) and a number of other Bolshevik newspapers were suppressed. A worker named Voinov was killed by cadets in the street merely for selling Listok Pravdy (Pravda Bulletin). Disarming of the Red Guards began. Revolutionary units of the Petrograd garrison were withdrawn from the capital and dispatched to the trenches. Arrests were carried out in the rear and at the front. On July 7 a warrant was issued for Lenin's arrest. A number of prominent members of the Bolshevik Party were arrested.[5]

However, this was not enough to stop the spread of proletarian power:

In the interval from October 1917 to February 1918 the Soviet revolution spread throughout the vast territory of the country at such a rapid rate that Lenin referred to it as a "triumphal march" of Soviet power. The Great October Socialist Revolution had won.[5]

This established the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (RSFSR).

Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

Near the beginning of the RSFSR's existence, foreign imperialist powers — namely the United Kingdom, France, Japan, and the United States — intervened and attempted to destroy it alongside the domestic White Army, all at a time concurrent with the First World War.

This began with British and French troop capturing the northern coastal cities of Archangel and Murmansk with the aid of local White guard forces. In this area, imperialist and counter-revolutionary forces established a puppet government to facilitate their occupation. Japanese troops would also invade the country from the Far-Eastern city of Vladivostok. By the 1920s however, the imperialist invaders were forced to withdraw.[5]

In December 1922, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was established with its first Union Republics being the Russian Soviet Federative Soviet Republic, Trancaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. From its inception, the USSR was developed on a voluntary and equal basis between nationalities and Union Republics, with them reserving the right to freely secede in accord with the will of their population.[7] It was among the first long-lasting socialist states in the world.

Socialist construction and early Soviet Union (1922–1953)

Death of Lenin and New Economic Policy

After the establishment of the USSR, Lenin would die in 1924. Before this, he had suffered several strokes and was under the care of his closest comrade, Joseph Stalin. After Lenin's death, Stalin replaced him, and led the Soviet Union. While the death of Lenin was a setback for the revolution, it was recoverable. Lenin's successor, Stalin, was another proletarian revolutionary who was able to guide the USSR to socialism.

The Soviet government continued the New Economic Policy which was in effect since 1921 and would discontinue it in 1928, beginning the initial five-year plan.

Great Break and first five-year plans

Stalin's Struggle Against Opportunism

However, when Stalin took control of the USSR, the fight against Menshevism and other variants of opportunism were not concluded. Its modern varieties, namely Trotskyism, still fought against the Bolshevik party and attempted to wage bourgeois struggle against it.[c] This struggle culminated in the murder of Sergei Kirov in 1934 by a Trotskyist terror group.

However, these assassins[d] were quickly discovered, and they were put to trial and executed in 1936.

Yezhovchina

In 1936-1938, a counter-revolutionary called Nikolai Yezhov raged terror against the Soviet populace behind Stalin's back, using false evidence for arrests and imprisoning many. However, Stalin soon caught on to this, and arrested Yezhov for these crimes, while freeing the innocent. Anti-Stalinists often maintain that the amount of those innocent that were arrested was higher than it actually was, while somehow maintaining at the same time that when Yezhov was put to trial for these crimes, it was a “show trial”.

Great Patriotic War

In 1939, a new world war broke out, which, through the idle behavior of the major bourgeois-democratic powers, became a war of fascism against socialism. Through the intelligent tactics and valor of the Soviet people (including a non-aggression pact which allowed them to build up their defenses), the Nazi-led invasion of the Soviet Union was repelled and the war ultimately won by socialist and anti-fascist forces, and fascism suffered a major defeat. By May 1945, the fascist forces surrendered and the war had concluded in Europe.

Revisionist era and restoration of capitalism (1953–1991)

Murder of Stalin and revisionist turn

In 1953, Stalin was murdered, and the USSR was put under the control of revisionists led by Nikita Khrushchev. Suddenly, revisionist concepts such as a "socialist state of the whole people" were enforced by the Soviet government. In the same year, COMECON[e] was weaponized with "specialization". In 1955, a social-imperialist organization commonly known as the Warsaw Pact was created, in order to militarily enforce the Soviet revisionist line. In 1956, the Soviet revisionists slandered Stalin and many other principled communists and initiated a counter-revolutionary program of "De-Stalinization". The sovereignty of nations became an empty phrase, and the Soviet Union became a global imperialist superpower. In 1964, with Khrushchev being ousted and succeeded by Leonid Brezhnev as leader, the social-imperialist nature of the Soviet union became more evident.[f]

Brezhnev era

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Leonid Brezhnev would become General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1964 after a military putsch. Under his 18 year rule of the Soviet Union, he retained most counter-revolutionary policies of his predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev, and greatly expanded the Soviet Union's social-imperialist aims, invading multiple countries. Furthermore, his leadership saw considerable increases in technocracy, bureaucratism, and corruption.[8]

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

By the mid-to-late 1980s, the Soviet Union was suffering from the long-term ramifications of capitalist restoration and revisionist rule. After years of leadership of the openly anti-communist politician Mikhail Gorbachev and his clique, the need for the revived Soviet bourgeoisie to maintain the outward façade of socialism disappeared. The Soviet Union would be torn apart by ethnic conflict and nationalism, leading to multiple Union republics succeeding from the Union by the end of the 1980s.

Following the rise of reactionary Russian nationalist Boris Yeltsin to leadership of the Russian SFSR and a failed coup d'état attempt in August 1991, the remaining power of the revisionist CPSU under Mikhail Gorbachev had dissipated and the party was banned in November 1991. This led to the official dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991. The Soviet Union was divided between its former Union republics, now made independent states, with the largest being the Russian Federation.

Economics

The Soviet Union prior to 1956 was a socialist planned economy which operated in the interests of the working class. The Soviet economy was premised on the collectivization of private ownership into public ownership (either through the state or cooperatives) and production based on a rational economic plan. By 1941, the state owned tens of thousands of industrial enterprises, over 10,000 agricultural enterprises, over 170,000 kilometers of rail and water ways, and over 350,000 trading enterprises. In the Soviet Union, the need for collectivization required the state to directly own many agricultural areas. However, state control in a socialist control like the USSR was simply an indirect form a control by the people.[9]

Employment

Unemployment was widespread during the NEP period, but disappeared during socialist construction and did not return until the full restoration of capitalism after the 1950s. People who studied for a higher education had to go into a certain line of work for a few years as compensation for the state educating them, after which they were free to work other jobs.[10]

Pre-revolutionary background

In 1917, Russia was a backwards semi-capitalist and feudal society. They had only recently abolished the manor system and serfdom, replacing it with the most brutal and primitive form of capitalism. The nation was dreadfully underdeveloped, with no sign of improving in the future, and what little growth did occur led to massive inequalities. According to a professor of economic history at Oxford University:

Not only were the bases of Imperial advance narrow, but the process of growth gave rise to such inequitable changes in income distribution that revolution was hardly a surprise. Real wages for urban workers were static in the late Imperial period despite a significant increase in output per worker[.] The revolution was also a peasant revolt, and the interests of the peasants were different[.] As in the cities, there was no gain in real wages.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

The University of Warwick corroborates these observations:

Agriculture had reached North American levels of productivity by 1913 and wheat prices collapsed after 1914. The expansion of the railroads had run its course and there was no prospect of protected light industry becoming internationally competitive. The appropriate comparators for the prospects for Russian capitalism in the twentieth century are not Japan but Argentina or even India. Moreover, Russian capitalist development had brought little if any benefit to the urban and rural working class, intensifying the class conflicts that erupted in Revolution.

— Simon Clarke, [12]

Early period

With the 1917 revolution (and after the bloody civil war, with its policy of war communism), the Soviet economy began to grow rapidly.[13] The New Economic Policy (which nationalized large-scale industry and redistributed land, while allowing for the private sale of agricultural surplus) succeeded in transforming Russia from a semi-capitalist existence into a developing state capitalist society, laying the groundwork for a socialist planned economy.

Following War Communism, the New Economic Policy (NEP) sought to develop the Russian economy within a quasi-capitalist framework.

— Simon Clarke, [12]

Economic circumstances came to require the transition to a planned economy:

However, the institutional and structural barriers to Russian economic development were now compounded by the unfavorable circumstances of the world economy, so that there was no prospect of export-led development, while low domestic incomes provided only a limited market for domestic industry. Without a state coordinated investment program, the Soviet economy would be caught in the low-income trap typical of the underdeveloped world.

— Simon Clarke, [12]

In 1928 (after they selected the new head of the Communist Party), the RSFSR instituted a fully planned economy, and the first Five Year Plan was enacted. This resulted in rapid economic growth:

Soviet GDP increased rapidly with the start of the first Five Year Plan in 1928. […] The expansion of heavy industry and the use of output targets and soft-budgets to direct firms were appropriate to the conditions of the 1930s, they were adopted quickly, and they led to rapid growth of investment and consumption.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

Bourgeois economists often alleged that this rapid growth came at the cost of per-capita consumption and living standards. However, more recent research has shown this to be false:

There has been no debate that ‘collective consumption’ (principally education and health services) rose sharply, but the standard view was that private consumption declined. Recent research, however, calls that conclusion into question. […] While investment certainly increased rapidly, recent research shows that the standard of living also increased briskly. […] Calories are the most basic dimension of the standard of living, and their consumption was higher in the late 1930s than in the 1920s. […] There has been no debate that ‘collective consumption’ (principally education and health services) rose sharply, but the standard view was that private consumption declined. Recent research, however, calls that conclusion into question. […] Consumption per head rose about one quarter between 1928 and the late 1930s.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

From Farm to Factory: A Reinterpretation of the Soviet Industrial Revolution by Robert C. Allen contains a good defense of collectivization, rebutting the claim that the same level of industrialization could have been achieved by continuing the NEP.

Calorie consumption rose rapidly during this period:

Calories are the most basic dimension of the standard of living, and their consumption was higher in the late 1930s than in the 1920s. […] In 1895-1910, calorie availability was only 2100 per day, which is very low by modern standards. By the late 1920s, calorie availability advanced to 2500. […] By the late 1930s, the recovery of agriculture increased calorie availability to 2900 per day, a significant increase over the late 1920s. The food situation during the Second World War was severe, but by 1970 calorie consumption rose to 3400, which was on a par with western Europe.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

Overall, the development of the Soviet economy during the interwar period was extremely impressive:

The Soviet economy performed well. […] Planning led to high rates of capital accumulation, rapid GDP growth, and rising per capita consumption even in the 1930s. […] The expansion of heavy industry and the use of output targets and soft-budgets to direct firms were appropriate to the conditions of the 1930s, they were adopted quickly, and they led to rapid growth of investment and consumption.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

The USSR's growth during interwar period exceeded that of the market economies:

The USSR led the non-OECD countries and, indeed, achieved a growth rate in this period that exceeded the OECD catch-up regression as well as the OECD average.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

This success is also attributed specifically to the revolution and the planned economy:

This success would not have occurred without the 1917 revolution or the planned development of state owned industry.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

The benefits of the planned economy become obvious upon closer study:

A capitalist economy would not have created the industrial jobs required to employ the surplus labour, since capitalists would only employ labour so long as the marginal product of labour exceeded the wage. State-sponsored industrialization faced no such constraints, since enterprises were encouraged to expand employment in line with the demands of the plan.

— Simon Clarke, [12]

Economic growth was also aided by the liberation of women, and the resulting control over the birth rate, as well as women's participation in the workforce:

The rapid growth in per capita income was contingent not just on the rapid expansion of GDP but also on the slow growth of the population. This was primarily due to a rapid fertility transition rather than a rise in mortality from collectivization, political repression, or the Second World War. Falling birth rates were primarily due to the education and employment of women outside the home. These policies, in turn, were the results of enlightenment ideology in its communist variant.

— Robert C. Allen, [11]

Reviews of Allen's work have backed up his statements:

Allen shows that the Stalinist strategy worked, in strictly economic terms, until around 1970. […] Allen’s book convincingly establishes the superiority of a planned over a capitalist economy in conditions of labour surplus (which is the condition of most of the world most of the time).

— Simon Clarke, [12]

Other studies have backed-up the findings that the USSR's living standards rose rapidly:

Remarkably large and rapid improvements in child height, adult stature and infant mortality were recorded from approximately 1945 to 1970. […] Both Western and Soviet estimates of GNP growth in the Soviet Union indicate that GNP per capita grew in every decade in the postwar era, at times far surpassing the growth rates of the developed western economies. […] The conventional measures of GNP growth and household consumption indicate a long, uninterrupted upward climb in the Soviet standard of living from 1928 to 1985; even Western estimates of these measures support this view, albeit at a slower rate of growth than the Soviet measures.

— Williams College, [14]

As early as 1917, forest conservation became one of Bolshevism's duties.[15] With one minor exception, the Politburo consistently rejected the drive toward hyperindustrialism in the forest: Moscow capitulated only briefly to the industrialists in 1929, and in the 1930s and 1940s it set aside larger tracts of the RSFSR's most valuable forests as preserves, off-limits to industrial exploitation.[16]

Health

The USSR placed importance on the health of its people, and alongside quality food products, provided health care as a constitutional right.

ARTICLE 120. Citizens of the U.S.S.R. have the right to maintenance in old age and also in case of sickness or loss of capacity to work. This right is ensured by the extensive development of social insurance of workers and employees at state expense, free medical service for the working people and the provision of a wide network of health resorts for the use of the working people. - (Soviet Constitution of 1936 Chapter 10: FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF CITIZENS)[17]

Health conditions in Imperial Russia had been deplorable; it was among the unhealthiest nations in Europe, if not Earth in general:

Without doubt the Soviet Union was one of the most underdeveloped European countries at the time of the October Revolution. In terms of life-expectancy it lagged behind the other industrialized countries of Europe by a gap of about 15 years.

— University of Munich, [18]

However, after the October Revolution, healthcare conditions began to improve rapidly.[19] By the end of the interwar period, healthcare standards (measured by life expectancy and mortality rates) were superior to those of Western Europe and the USA:

One of the most striking advances of socialism has been and was generally seen to be the improvement in public health provision for the population as a whole. In accordance with this assumption mortality-rates in the Soviet Union declined rapidly in the first two decades after World War II. In 1965 life-expectancy for men and women in all parts of the Soviet Union, which still included vast underdeveloped regions with unfavorable living conditions, were as high or even higher than in the United States. Such a development fits perfectly into the picture of emerging industrial development and generally improving conditions of living.

— University of Munich, [18]

Even reactionary intellectuals were forced to acknowledge these achievements; according to Nick Eberstadt (an anti-communist think-tank adviser), healthcare standards in the Soviet Union during the interwar period surpassed those of the United and Western Europe:

Over much of this century the nation in the vanguard of the revolution in health was the Soviet Union. In 1897 Imperial Russia offered its people a life expectancy of perhaps thirty years. In European Russia, from what we can make out, infant mortality (that is, death in the first year) claimed about one child in four, and in Russia’s Asian hinterlands the toll was probably closer to one in three. Yet by the late 1950s the average Soviet citizen could expect to live 68.7 years: longer than his American counterpart, who had begun the century with a seventeen-year lead. By 1960 the Soviet infant mortality rate, higher than any in Europe as late as the Twenties, was lower than that of Italy, Austria, or East Germany, and seemed sure to undercut such nations as Belgium and West Germany any year.

— Nick Eberstadt

He even notes that these achievements made planned economics seem nearly indefatigable:

In the face of these and other equally impressive material accomplishments, Soviet claims about the superiority of their “socialist” system, its relevance to the poor countries, and the inevitability of its triumph over the capitalist order were not easily refuted.

— Nick Eberstadt

While health conditions did start to decline after the introduction of revisionist policies in the mid-1950s, this was likely caused mostly by the substance abuse, lopsided age demographics due to WWII, and the disparities in mortality rates between the European and Asian regions of the union rather than actual deficiencies in the healthcare system.[20] Either way, the planned economy's healthcare achievements remain unimpeachable.

Infrastructure

Railways

From 1927 to 1941, the USSR expanded their freight rail network to be 20x larger than before, surpassing the United States.

Society

Education

Already in 1919, despite the lackluster economic conditions, the communists improved education substantially:

Thousands of new schools have been opened in all parts of Russia and the Soviet Government seems to have done more for the education of the Russian people in a year and a half than Czardom did in 50 years. […] The achievements of the department of education under Lunacharsky have been very great. Not only have all the Russian classics been reprinted in editions of three and five million copies and sold at a low price to the people, but thousands of new schools for men, women, and children have been opened in all parts of Russia. Furthermore, workingmen’s and soldiers’ clubs have been organized in many of the palaces of yesteryear, where the people are instructed by means of moving pictures and lectures. In the art galleries one meets classes of working men and women being instructed in the beauties of the pictures. The children’s schools have been entirely reorganized, and an attempt is being made to give every child a good dinner at school every day. Furthermore, very remarkable schools have been opened for defective and over-nervous children. On the theory that genius and insanity are closely allied, these children are taught from the first to compose music, paint pictures, sculpt and write poetry, and it is asserted that some valuable results have been achieved, not only in the way of productions but also in the way of restoring the nervous systems of the children.

— William C. Bullitt, [21]

Corporal punishment, common in Imperial Russia, became illegal and increasingly rare.[22] Education continued to improve from the 1920s to the 1960s, and various non-socialist observers, including Western government officials, have attested to the high quality of Soviet education, noting the diverse range of subjects, support for students, and complexity compared to U.S. education.[23]

In common with primary and secondary education, all higher education is free, and students in higher education who maintain a ‘B’ average also receive a stipend. Such stipends vary according to the year of study, the subject studied, the type of school and the student’s progress; no stipend is paid for a year that must be repeated. In the mid-1970s university students received 40–60 roubles a month and technical school students 30–45 roubles. Admission to higher education is by examinations for specific institutions; there are no IQ tests or general aptitude tests in the USSR. Students who fail one institution’s entrance exam can reapply in future years or apply to other institutions. Advantages are given to higher education applicants with work experience, for example, quotas, extra points on examinations, special tutorial programmes. In 1967, 30% of admissions to higher education were of people who had been working full time. In general, Soviets are actively encouraged to continue with formal education throughout their lives. Indeed, the Soviets have one of the highest rates of attendance at institutions of higher education in the world.

— Albert Szymański, [24]

Geography

Political divisions

Union Republics

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was a federation of fifteen separate Union Republics, all of which existed on a voluntary and equal basis within the Union with full rights of succession.

| Emblem | Name | Flag | Capital | Official languages | Established | Union Republic status | Sovereignty | Independence | Population (1989) |

Pop. % |

Area (km2) (1991) |

Area % |

No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Yerevan | Armenian, Russian | 2 December 1920 | 5 December 1936 | 23 August 1990 | 21 September 1991 | 3,287,700 | 1.15 | 29,800 | 0.13 | 13 |

|

Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Baku | Azerbaijani, Russian | 28 April 1920 | 23 September 1989 | 18 October 1991 | 7,037,900 | 2.45 | 86,600 | 0.39 | 7 | |

|

Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Minsk | Byelorussian, Russian | 31 July 1920 | 30 December 1922 | 27 July 1990 | 25 August 1991 | 10,151,806 | 3.54 | 207,600 | 0.93 | 3 |

|

Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Tallinn | Estonian, Russian | 21 July 1940 | 6 August 1940 | 16 November 1988 | 8 May 1990 | 1,565,662 | 0.55 | 45,226 | 0.20 | 15 |

|

Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Tbilisi | Georgian, Russian | 25 February 1921 | 5 December 1936 | 18 November 1989 | 9 April 1991 | 5,400,841 | 1.88 | 69,700 | 0.31 | 6 |

|

Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Alma-Ata | Kazakh, Russian | 26 August 1920[g] | 25 October 1990 | 16 December 1991 | 16,711,900 | 5.83 | 2,717,300 | 12.24 | 5 | |

|

Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Frunze | Kirghiz, Russian | 11 February 1926[h] | 15 December 1990 | 31 August 1991 | 4,257,800 | 1.48 | 198,500 | 0.89 | 11 | |

|

Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Riga | Latvian, Russian | 21 July 1940 | 5 August 1940 | 28 July 1989 | 4 May 1990 | 2,666,567 | 0.93 | 64,589 | 0.29 | 10 |

|

Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Vilnius | Lithuanian, Russian | 3 August 1940 | 18 May 1989 | 11 March 1990 | 3,689,779 | 1.29 | 65,200 | 0.29 | 8 | |

|

Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Kishinev | Moldavian, Russian | 12 October 1924[i] | 2 August 1940 | 23 June 1990 | 27 August 1991 | 4,337,600 | 1.51 | 33,843 | 0.15 | 9 |

|

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic |

|

Moscow | Russian | 7 November 1917 | 30 December 1922 | 12 June 1990 | 12 December 1991 | 147,386,000 | 51.40 | 17,075,400 | 76.62 | 1 |

|

Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Dushanbe | Tajik, Russian |

14 October 1924[j] | 5 December 1929 | 24 August 1990 | 9 September 1991 | 5,112,000 | 1.78 | 143,100 | 0.64 | 12 |

|

Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Ashkhabad | Turkmen, Russian | 13 May 1925 | 27 August 1990 | 27 October 1991 | 3,522,700 | 1.23 | 488,100 | 2.19 | 14 | |

|

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Kiev | Ukrainian, Russian | 10 March 1919 | 30 December 1922 | 16 July 1990 | 24 August 1991 | 51,706,746 | 18.03 | 603,700 | 2.71 | 2 |

|

Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic |

|

Tashkent | Uzbek, Russian |

5 December 1924 | 20 June 1990 | 1 September 1991 | 19,906,000 | 6.94 | 447,400 | 2.01 | 4 | |

Environment

The USSR produced so little plastic that it was essentially non-existent, and the plastic that was produced was made to last. Most bottles were made of glass, with old ones sent to factories to be sanitized and reused, with broken glass either swept up to be melted down or otherwise disposed of. Metal and paper waste was treated just like in wartime, similar to the US scrap collection system during World War II, resulting in minimal metal and paper waste. Littering was fined and weekly cleanup volunteers helped reduce trash in public places.

Widespread availability and use of public transport meant less CO2 produced as well. Cars also tended to have 4-6 cylinders meaning they used less gas, with trucks using diesel fuel which requires less refinement and is thus cheaper, while also using less energy from power plants.

The focus on nuclear power further reduced CO2 emissions, with nuclear power gradually coming to supersede coal-based power. Windmills were also used in areas for water pumps and flour production. And furthermore Stalin, for one, had a series of ecological programs which replanted thousands of square kilometers of forests cut down or destroyed in preparation for and during World War II - The Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature (1948-1953). In all these ways, the Soviets sought to reduce the ecological effects of their rapid and massive industrialization necessary to survive their early years as a nation.

The Russian Federation, on the other hand, shirked environmental maintenance work which was regularly done in the USSR. The current system is to cut down a section of forest, dig a deep pit, dump waste in the pit, light it on fire, and then bury it while the methane and other fuel continue to let the fire burn under ground; leaking into the air and nearby villages. This has caused and still causes large protests, especially since this is a significant step down from the more efficient trash sorting and processing system present in the Soviet Union.

Aral Sea

Aral Sea has been slowly drying up for a while naturally. If no humans effect it this would take a few millennia to eliminate. Obviously human impact has sped up this process. In the 1960s, Soviet researchers predicted the complete evaporation of the body of water, and a river used to irrigate farmland had the excess water siphoned into the lake and would have been rerouted to continue to do so. This was, however, expensive, and during the privatizations (and subsequent economic catastrophe) of the 1980s, that came with the rise of Gorbachev, the plan was abandoned. After Kazakhstan seceded, high-intensity cotton farming practices and infrastructure mismanagement - most water running through irrigation to the farms evaporated on the way there - accelerated the shrinkage. Most of the former Aral Sea is a desert. The destruction of the Aral Sea is a product of resource mismanagement both during the period of capitalist restoration in the Soviet Union and after, with the latter being exemplified by Yeltsin's capitalist shock therapy which largely disregarded environmental sustainability rather than simple ignorance of impact.

Radioactive dumping

There is only one lake with high radiation levels as a result of radioactive dumping, Lake Karachay, but that was because radiation was not understood nearly as well at the time. Similarly, radioactive dumping by Soviets has occurred in the Barents and Kara Seas, however this was not a phenomenon unique to the USSR.[25]

See also

- Great October Socialist Revolution

- All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

- Republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union

References

- ↑ Демоскоп Weekly.Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения пореспубликам СССР [The 1989 All-Union Population Census. National composition of the population by republics of the USSR].

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 CIA World Factbook (1990). Soviet Union – World Factbook (Wikisource)

- ↑ CIA World Factbook (1991). [https://www.theodora.com/wfb1991/soviet_union/soviet_union_economy.html Soviet Union Economy]

- ↑ CIA World Factbook (1990). GDP per Capita 1990

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 History of the CPSU(B): Short Course. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1939/x01/

- ↑ One Step Forward, Two Steps Back. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1904/onestep

- ↑ Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1922).

- ↑ Enver Hoxha (1969). The Demagogy of the Soviet Revisionists Cannot Conceal Their Traitorous Countenance.

- ↑ A. Kursky (1949). The Planning of the National Economy of the USSR.

- ↑ Is the Red Flag Flying? The Political Economy of the Soviet Union, pages 46-50

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 18.0 18.1

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Ocean disposal of radioactive waste

Notes

- ↑ Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик (CCCP)

- ↑ Russian: Советский Союз

- ↑ The namesake of Trotskyism, Trotsky, later also collaborated with Nazi Germany and fascist Japan.

- ↑ Including Trotsky himself.

- ↑ A socialist organization that provided mutual economic assistance between socialist countries. Became a social-imperialist organization in 1953.

- ↑ See the Soviet response to the Hungarian and Czechoslovak counter-revolutions, and the reasons this response occurred.

- ↑ As Kazak ASSR.

- ↑ As Kirghiz ASSR.

- ↑ As Moldavian ASSR.

- ↑ As Tajik ASSR.