The Communist Manifesto

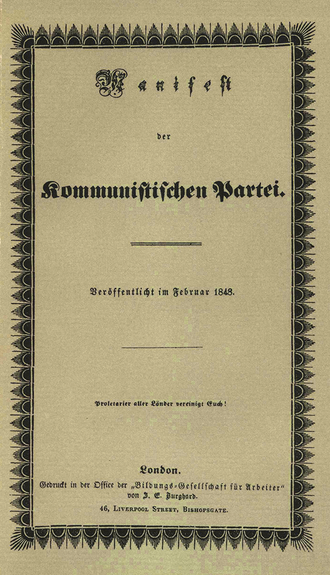

Cover of the work in the first German edition. | |

| Authors |

Karl Marx Friedrich Engels |

|---|---|

| Original title | Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei |

| Publication year | 1848 |

| Subject | Fundamental aspects of communism |

| Media type | Manifesto |

| Preceded by | The Principles of Communism |

| A library version of The Communist Manifesto is available. |

The Communist Manifesto [a] is an early communist pamphlet commissioned by the Communist League, written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1847, and published in 1848. The book consists of a systematic exposition of the ideas and aims of the Communists at that time. As such, the work contains brief explanations of the materialist conception of history, class struggle, and so on. It is divided into four chapters and largely based on Engels' Principles of Communism, the second draft of the Manifesto, with Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith being the first.

The Communist Manifesto has become the most famous and widely-read work of Marx and Engels; however, many Marxists consider it to be an outdated picture of Marx's ideas, espousing many erroneous positions — such as the imminent annihilation of the middle class, which Marx later revised in an 1863 manuscript[b] — that did not reflect later Marxist theory. It nevertheless retains considerable influence in the mainstream perception of Marxist and communist ideas.

Summary

It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the Spectre of Communism with a manifesto of the party itself.

I: Bourgeois and Proletarians

Marx and Engels detail the history of society as being that of class struggle. From this, they transition to detailing the development of industrial capitalism, decline of agrarian feudalism, and the forms of class conflict in the new society — between the proletariat and bourgeoisie.[1]

"The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes."

II: Proletarians and Communists

Marx and Engels detail the aspects of communism, how communists are to relate to other socialist movements and the working class broadly. They further refute bourgeois defenses of the capitalist system.[2]

"The distinguishing feature of Communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property. But modern bourgeois private property is the final and most complete expression of the system of producing and appropriating products, that is based on class antagonisms, on the exploitation of the many by the few.

In this sense, the theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property."

III: Socialist and Communist Literature

Marx and Engels elaborate various tendencies which present themselves as socialist and note their failings and limitations. In order, they write on reactionary socialists, petty-bourgeois socialists, German or true socialists, and conservative socialists. They conclude by addressing the utopian socialist tendency.[3]

"In political practice, therefore, [reactionary socialists] join in all coercive measures against the working class; and in ordinary life, despite their high-falutin phrases, they stoop to pick up the golden apples dropped from the tree of industry, and to barter truth, love, and honor, for traffic in wool, beetroot-sugar, and potato spirits"

"[...] [Petty-bourgeois socialism] aspires either to restoring the old means of production and of exchange, and with them the old property relations, and the old society, or to cramping the modern means of production and of exchange within the framework of the old property relations that have been, and were bound to be, exploded by those means. In either case, it is both reactionary and Utopian.

Its last words are: corporate guilds for manufacture; patriarchal relations in agriculture."

"While this 'True' Socialism thus served the government as a weapon for fighting the German bourgeoisie, it, at the same time, directly represented a reactionary interest, the interest of German Philistines. In Germany, the petty-bourgeois class, a relic of the sixteenth century, and since then constantly cropping up again under the various forms, is the real social basis of the existing state of things."

"The Socialistic bourgeois want all the advantages of modern social conditions without the struggles and dangers necessarily resulting therefrom. They desire the existing state of society, minus its revolutionary and disintegrating elements. They wish for a bourgeoisie without a proletariat. The bourgeoisie naturally conceives the world in which it is supreme to be the best; and bourgeois Socialism develops this comfortable conception into various more or less complete systems. In requiring the proletariat to carry out such a system, and thereby to march straightway into the social New Jerusalem, it but requires in reality, that the proletariat should remain within the bounds of existing society, but should cast away all its hateful ideas concerning the bourgeoisie."

IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties

In this concluding chapter, Marx and Engels describe working class and revolutionary movements which communists must ally with to achieve short-term objectives. These movements include the Chartists in the United Kingdom, Agrarian Reformers in the United States as well as the French social-democrats. They proceed to detail the tasks of communists in other countries, namely Switzerland, Poland, and the German states.[4]

The work concludes with the famous rallying cry "workers of the world, unite!".[c]

"The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.

Workers of the world, unite!"

"Ten planks of communism"

There is a section in Chapter II: Proletarians and Communists that describes ten "generally applicable" measures in the installation of the dictatorship of the proletariat, known commonly as the "ten planks of communism" though not known by any name within the Manifesto itself. They should be read in the context of their time, as most modern communists, taking changed historical conditions into account, do not propose to actually implement the policies they describe as described in the Manifesto. They are:

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

- Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

- Centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

- Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.

- Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children's factory labour in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, etc., etc.

From the preface of the 1872 German edition:

However much that state of things may have altered during the last twenty-five years, the general principles laid down in the Manifesto are, on the whole, as correct today as ever. Here and there, some detail might be improved. The practical application of the principles will depend, as the Manifesto itself states, everywhere and at all times, on the historical conditions for the time being existing, and, for that reason, no special stress is laid on the revolutionary measures proposed at the end of Section II. That passage would, in many respects, be very differently worded today. In view of the gigantic strides of Modern Industry since 1848, and of the accompanying improved and extended organization of the working class, in view of the practical experience gained, first in the February Revolution, and then, still more, in the Paris Commune, where the proletariat for the first time held political power for two whole months, this programme has in some details been antiquated. One thing especially was proved by the Commune, viz., that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” (See The Civil War in France: Address of the General Council of the International Working Men’ s Association, 1871, where this point is further developed.) Further, it is self-evident that the criticism of socialist literature is deficient in relation to the present time, because it comes down only to 1847; also that the remarks on the relation of the Communists to the various opposition parties (Section IV), although, in principle still correct, yet in practice are antiquated, because the political situation has been entirely changed, and the progress of history has swept from off the earth the greater portion of the political parties there enumerated.[5]

Thus the principles themselves are valid, though the methods and steps have in many regards become less applicable to modern conditions.

See also

References

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848). The Communist Manifesto, I. "Bourgeois and Proletarians".

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848). Ibid., II. "Proletarians and Communists".

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848). Ibid., III. "Socialist and Communist Literature".

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848). Ibid., IV. "Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties".

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848). Ibid., Preface.

Notes

- ↑ German: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei; "Manifesto of the Communist Party"

- ↑ Published posthumously as Theories of Surplus Value.

- ↑ German: "Proletarier aller Länder, vereinigt Euch!". Literally "Proletarians of all countries, unite!".